How useful has an ideological critical approach been in analysing the films you have studied? Refer in detail to one or more sequences from each film.

Autumn 2021

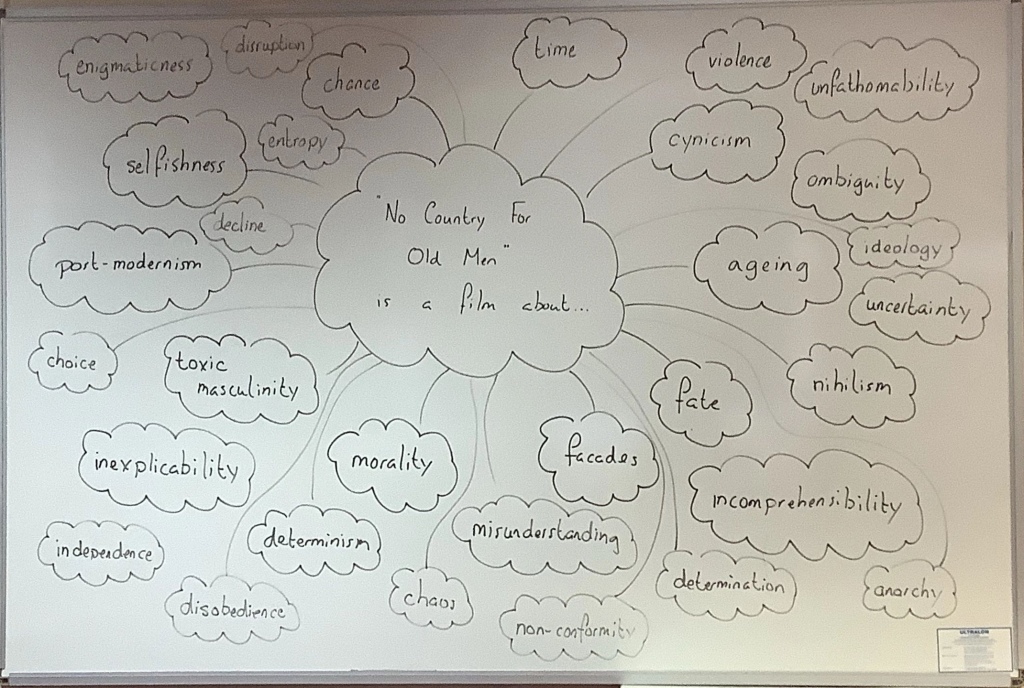

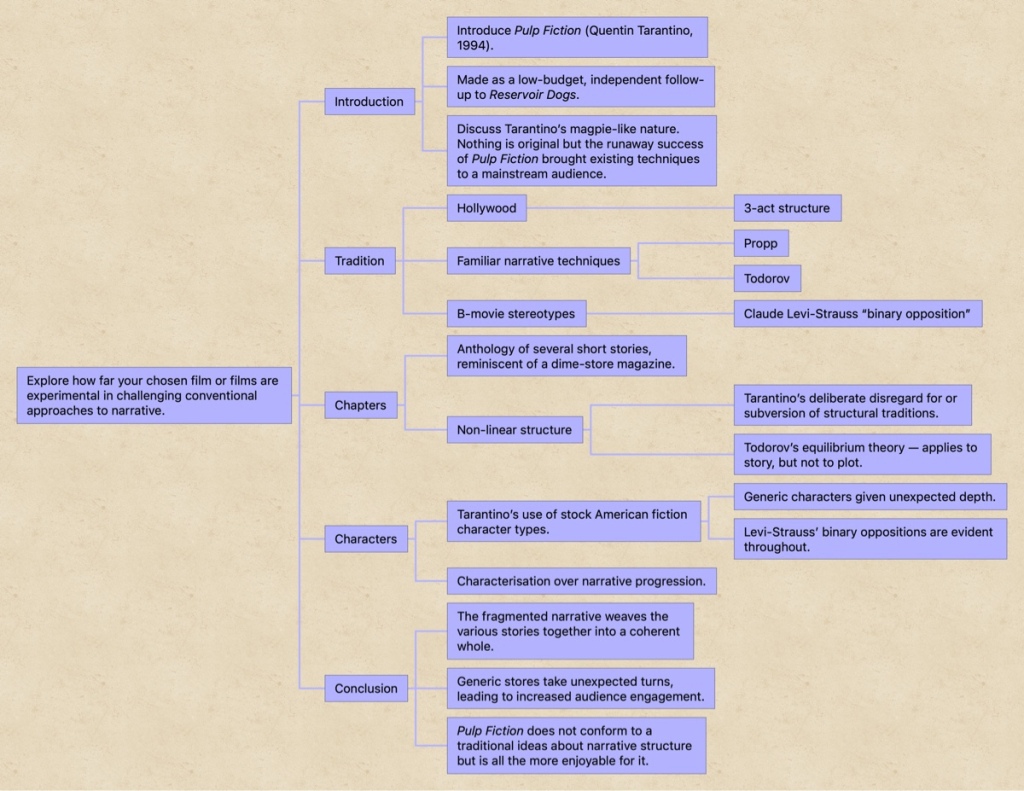

Plan:

Introduction

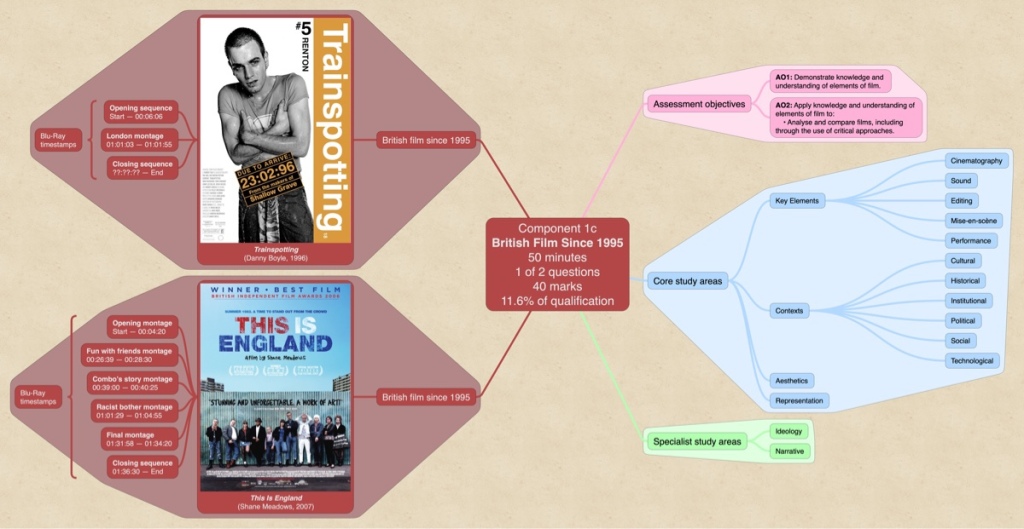

An ideological critical approach is often a highly insightful lens through which a film can be evaluated. In essence, considering ideological implications can enrich the meanings that are able to be extracted from a film’s thematic tapestry. Trainspotting (Danny Boyle, 1996) is a highly frenetic film showcasing the Edinburgh drug culture throughout the 1990s in a nonlinear fashion. The film moves at a blistering pace, prioritising the task of immersing the viewer within its world. Because of this, the film’s ideological messaging is notably ephemeral – fluctuating between themes of anti-consumerism, hedonism, and capitalism. In contrast, This is England (Shane Meadows, 2007) offers a clear-cut narrative with a strong anti-nationalist ideological underpinning, telling a single story that serves to critique the Thatcherism of the 1980s.

Body

Trainspotting – fluctuating ideology: anti-consumerist, hedonist, capitalist

- Cold open – Lust for Life lyrics, “choose life” monologue, Sick Boy heroin bliss

- The liberal zeitgeist of the 1990s – exaggerated mise-en-scène in drug den, harsh reds, reinforce the effects of drug use

- Boyle critiques the consumerist society that perpetuates drug addiction and poverty – encouraging audience empathy

- London Montage – cliched sights of London reinforces superficiality. A visual embodiment of Renton’s prior montage – the emptiness of consumerism and conformity. Despite a change in location, Renton is trapped in a consumerist vicious circle – systemic problems of society

- Closing sequence is a showcase of Renton’s rejection of hedonism and nihilism – final mirroring monologue

This is England – anti-nationalist

- Opening montage – newsreel archival footage grounds the film in Britain during the 1980s. Highlights the economic and social issues that led to the permeation of nationalism. Shaun’s impoverished, fatherless way of life is as a result of the events portrayed in the montage.

- Use of soul and reggae music creates a juxtaposition with the violent imagery on screen. Inherent contradictions within skinhead movement, encourages the audience to question the validity of Combo’s ideology

- Thatcherism – working class resentment towards controversial policies, embracing capitalism and shutting down coal mines. Iranian embassy crisis.

- Cultural and racial inclusivity – younger, older

- Combo’s entrance – malice and bigotry is revealed through exaggerated enunciation of racial epithets. Representative of the plague of nationalism during the 1980s. Handheld cameras focus in on a closeup, contrast gliding Steadicam during montage

- Racist bother montage – gliding and graceful camerawork. Portraying skinheads as simultaneously pathetic and threatening. Powerful critique of indoctrination – Shaun’s gradual descent into racist culture

- Newsreel montage – implicit commentary on the dangers of patriotism. Footage displays a solider erecting a British flag in a tiny village – viewer encouraged to question the validity of the British victory

- Symbolism of Shaun rejecting nationalism – throwing flag in ocean. Meadows does not leave his anti-nationalist message up for interpretation or debate

Conclusion

In conclusion, viewing Trainspotting through the lens of an ideological critical approach reveals the film’s attempt to comically deconstruct the messages that are typically conveyed to the youth. Despite the film’s ideological ambiguity, taking this particular approach has been useful in unravelling the thematic substance of the film. Conversely, employing an ideological critical approach for This is England allows for the film’s unashamed anti-nationalist ideology to be fully comprehended, encouraging us to question the nationalism and indoctrination that pervaded England during the 1980s.

Essay – Version 1

An ideological critical approach is often a highly insightful lens through which a film can be evaluated. In essence, considering ideological implications can enrich the meanings that are able to be extracted from a film’s thematic tapestry. Trainspotting (Danny Boyle, 1996) is a highly frenetic film showcasing the Edinburgh drug culture throughout the 1990s in a nonlinear fashion. The film moves at a blistering pace, prioritising the task of immersing the viewer within its world. Because of this, the film’s ideological messaging is notably ephemeral – fluctuating between themes of anti-consumerism, hedonism, and capitalism. In contrast, This is England (Shane Meadows, 2007) offers a clear-cut narrative with a strong anti-nationalist ideological underpinning, telling a single story that serves to critique the Thatcherism of the 1980s.

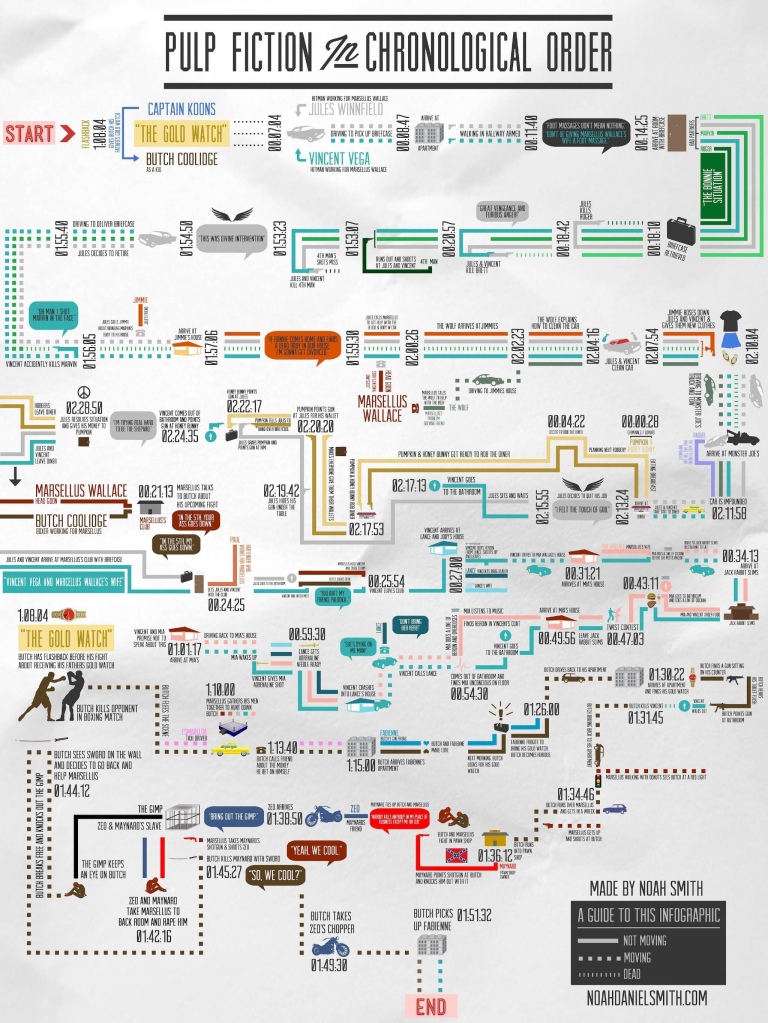

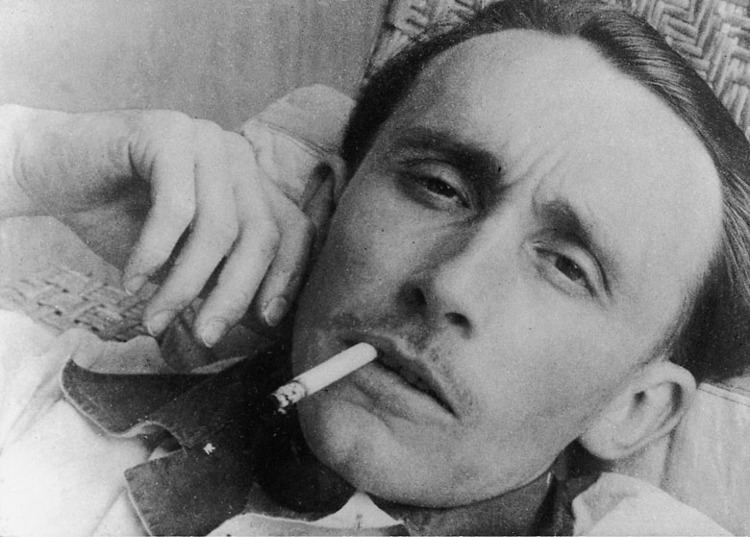

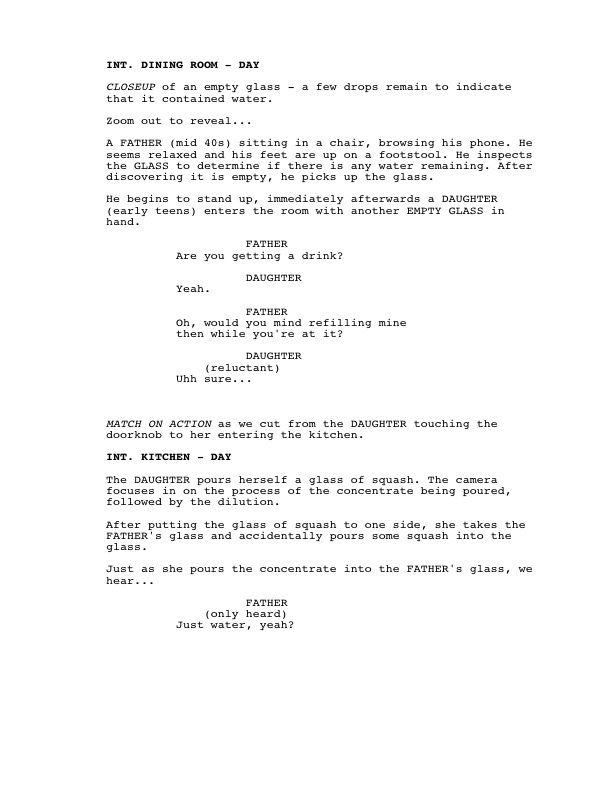

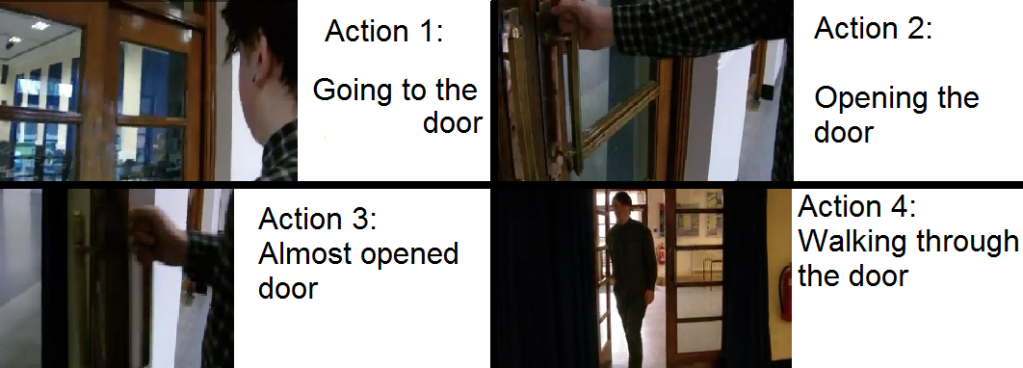

Trainspotting begins with a jarring cold open, beginning in medias res with an establishing wide shot of Renton and Spud fleeing from the authorities down the streets of Edinburgh. This frenetic opening is accompanied by the non-diegetic compiled score – Iggy Pop’s Lust for Life – a punk song from the 1970s that is aptly representative of the hedonistic lifestyle led by the characters. As we continue to follow Renton, we are subjected to non-diegetic narration – Renton’s iconic “choose life” monologue. The monologue provides a counter-culture message, rejecting societal norms and expectations, parodying the Scottish anti-drug mantra, instead glorifying the characters’ alternative lifestyles. This opening scene appeals to young defiant individuals, representing the liberal zeitgeist of the 1990s.

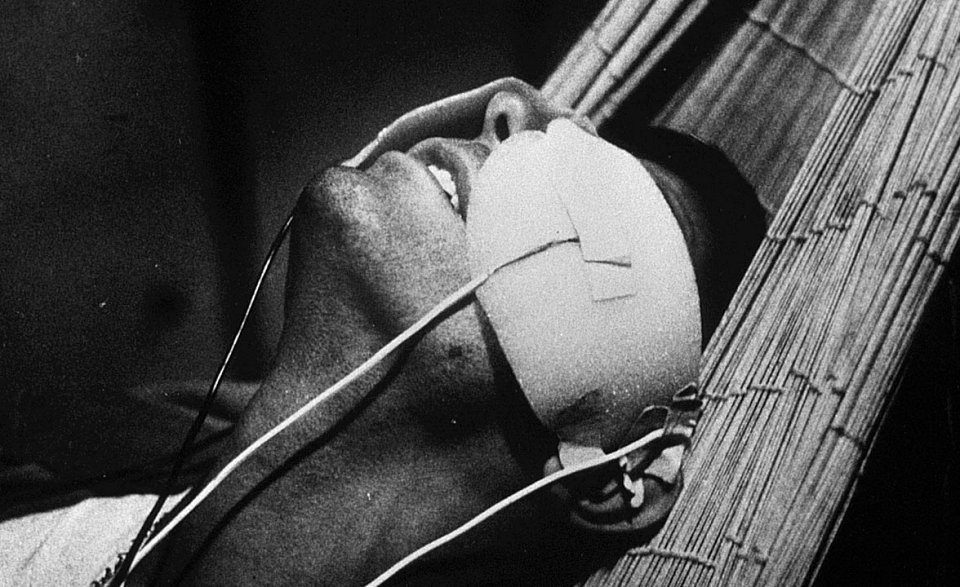

Scenes of the chase are intercut with scenes of Mother Superior’s drug den, during which the camera focuses in on a closeup of Sick Boy taking heroin, emphasising the hedonism embraced by the characters. In addition, the mise-en-scène within the den is notably heightened and exaggerated. Boyle’s use of harsh reds arguably reinforces an anti-capitalist ideology, symbolising the characters’ bleak, impoverished existence. By taking an anti-consumerist ideological approach, the audience is able to infer that an inherently consumerist society ultimately perpetuates drug addiction and poverty. This encourages the audience empathise with the characters’ struggles, causing the spectator to question the capitalist system that creates such inequalities.

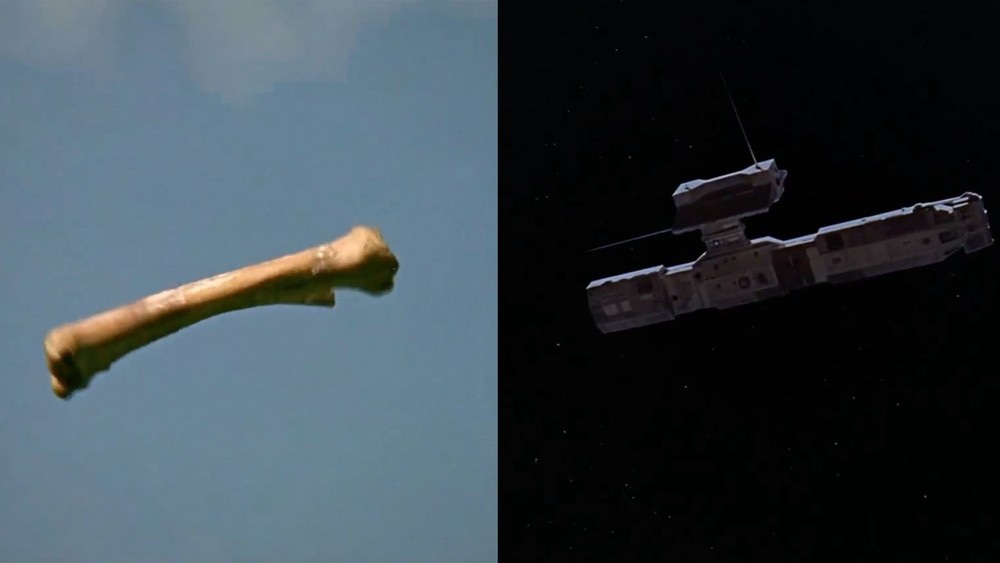

The London montage that occurs near the midpoint of the film also serves to reinforce an anti-capitalist ideology. The montage quickly cuts between a multiplicity of cliched sights associated with London, including Tower Bridge, ice cream, pigeons, and Piccadilly Circus. All of these serve to represent the superficiality of the city’s supposed capitalist agenda, which is reinforced by an arguably ‘soulless’ non-diegetic compiled EDM score that serves to epitomise the contemporary mainstream of the 1990s. The montage serves as a visual embodiment of the aforementioned “choose life” monologue, demonstrating the emptiness of consumerism and conformity. Despite the fact that Renton has ostensibly left his old lifestyle in Edinburgh behind, he is still trapped in a similar vicious circle. Irony is created from the fact that that while Renton has escaped from the drug den, he has entered into a new realm of capitalism and consumerism by becoming an estate agent, that is just as dangerous in his eyes. This highlights the film’s overarching ideological trappings, illustrate that the issues created by capitalism are systemic and cannot be solved by a simple change of scenery.

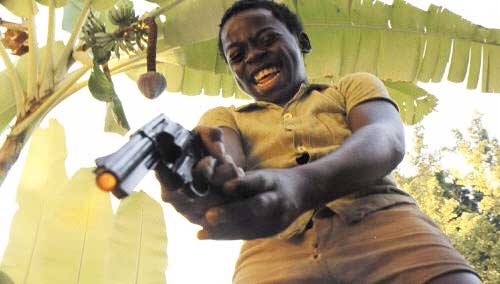

Trainspotting’s closing sequence perhaps best underpins the film’s oscillating ideological messaging, depicting Renton’s final decision to reject hedonism. Renton’s decision to steal the money represents the inevitable embrace of a capitalist system, suggesting that he is finally leaving his life of nihilism. Renton ultimately “chooses life” by taking the money for himself, realising that hedonism does not lead to true fulfilment in life. This is displayed to the viewer through a focus pull into a closeup that reveals Renton walking away with the money. Through the use of non-diegetic narration, Renton pledges to begin living a disciplined life, mirroring the rhythm and cadence of his initial “choose life” monologue. Renton states, “I’m gonna be just like you.”, forcing the audience to question their preconceptions towards society, encouraging them to question the status quo.

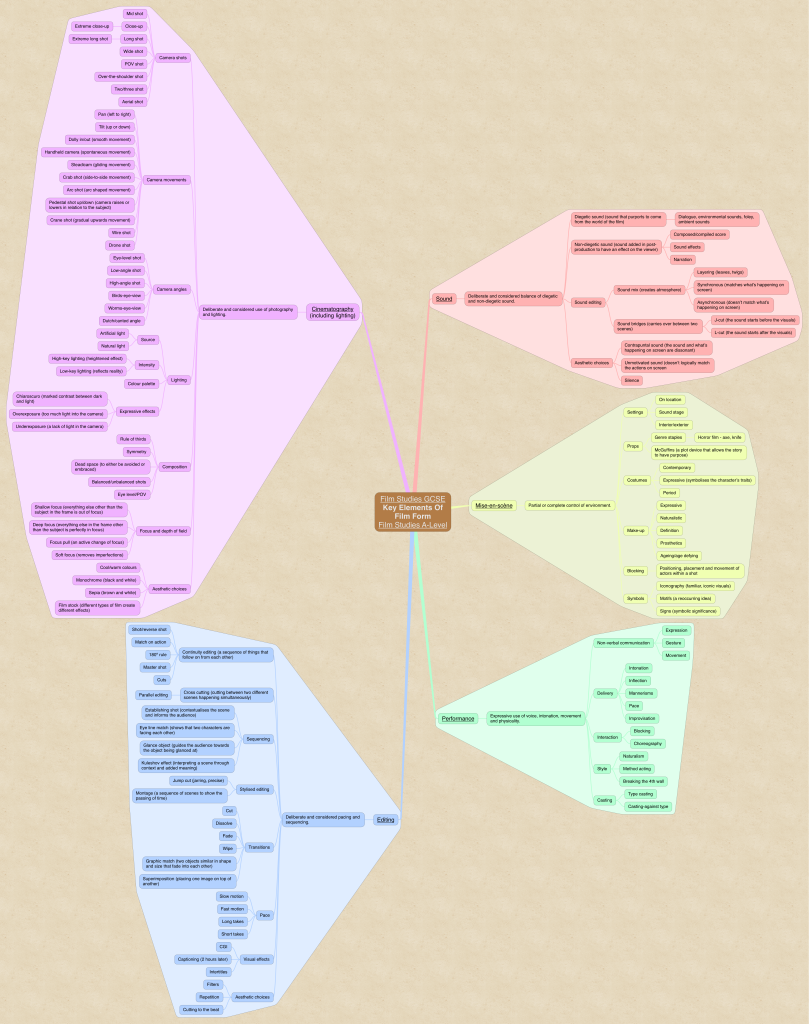

Conversely to Trainspotting’s cold open, This is England begins with a montage made up of newsreel archival footage. This serves to ground the film in Britain during the 1980s, highlighting the economic and social issues that led to the permeation of nationalism throughout the country, establishing the film’s anti-nationalist ideology. The montage draws particular attention to the Margaret Thatcher government and the rise of far-right politics in England. This included groups such as the National Front, a political party known for its racist rhetoric and violent actions, briefly displayed in the opening montage. The montage also showcases working-class resentment towards Thatcherist policies, involving the embrace of capitalism and the shutting down of coal mines. This footage is accompanied by a non-diegetic compiled reggae song, creating a juxtaposition when apposed with the violent imagery on screen. This song also encourages the audience to question the inherent contradictions within the skinhead movement – a movement originating from a shared love of music associated with black culture that was later plagued by racism and nationalism. After the montage, a title card establishes the year, 1983, and we are introduced to the main protagonist, Shaun. The viewer then is able to make the connection between Shaun’s impoverished, fatherless way of life, and the events portrayed in the montage – Shaun’s life is a direct result of the Thatcher government.

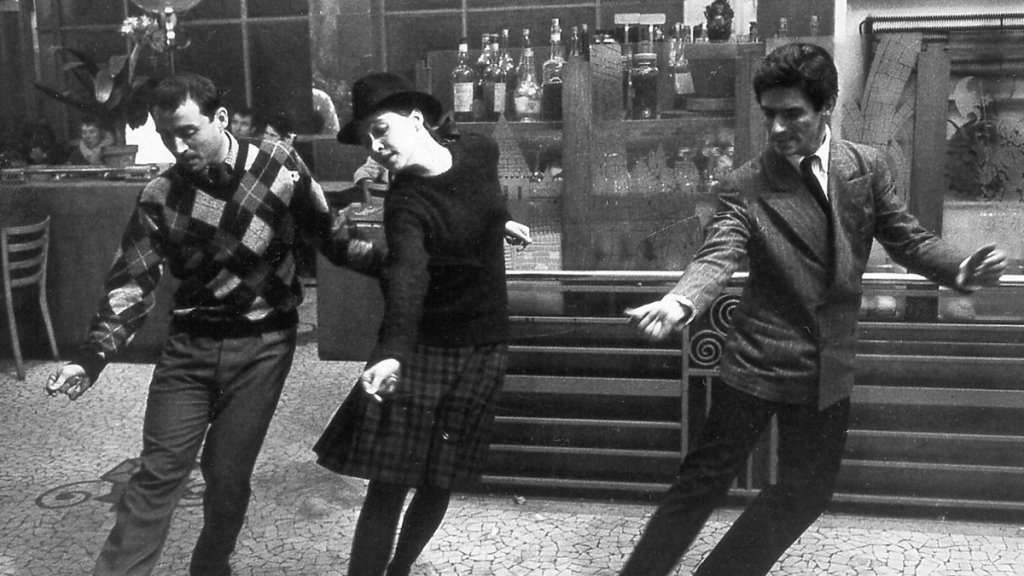

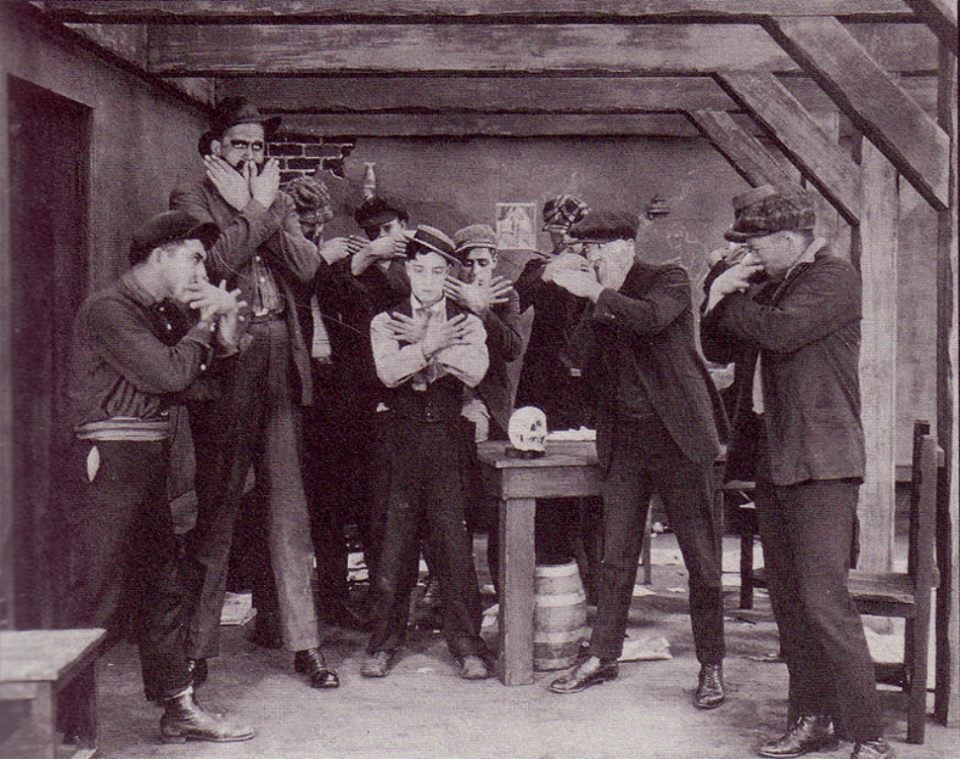

Soon afterwards, Shaun is taken under the wing of the skinheads and Meadows implements the use of another montage to illustrate the budding connection between them. Once again, the montage is accompanied by a reggae piece – a genre that emerged in Jamaica as a form of resistance to colonialism. In addition, the wide shot of the gang walking towards the camera displays the inclusive nature of the skinheads. The gang is notably diverse – being racially inclusive, having younger and older members, alongside male and female members. This challenges a nationalist ideology that typically campaigns for a homogenous, racially pure nation.

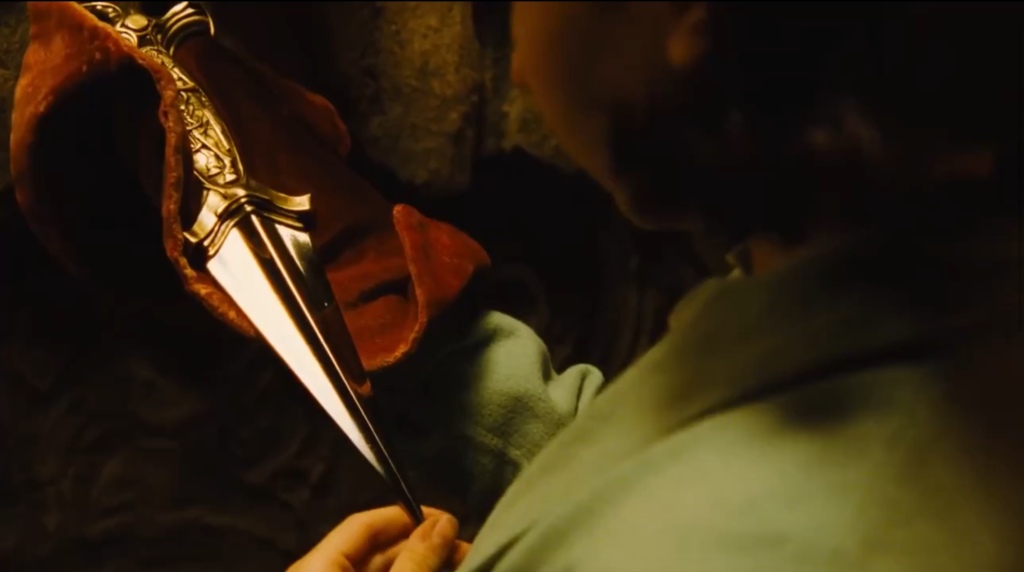

The sequence in which we are introduced to Combo is important to consider when taking an ideological critical approach. Combo’s malice and bigotry towards racial minorities is reinforced through his emphasised enunciation of racial epithets. Meadows’ use of handheld cameras contrasts the gliding Steadicam shots during the preceding montage, focusing in on a closeup of Combo to emphasise his raw and unpolished nature. As Combo proceeds to tell his story, the non-diegetic piano score is particularly manipulative, being an exception to the film’s footing in British social realism, emphasising the emotional impact of Combo’s bigoted remarks on the audience. Meadows’ intentions are to make the audience condemn Combo’s actions, highlighting the negative consequences of nationalism and racism within the bigger picture of the country.

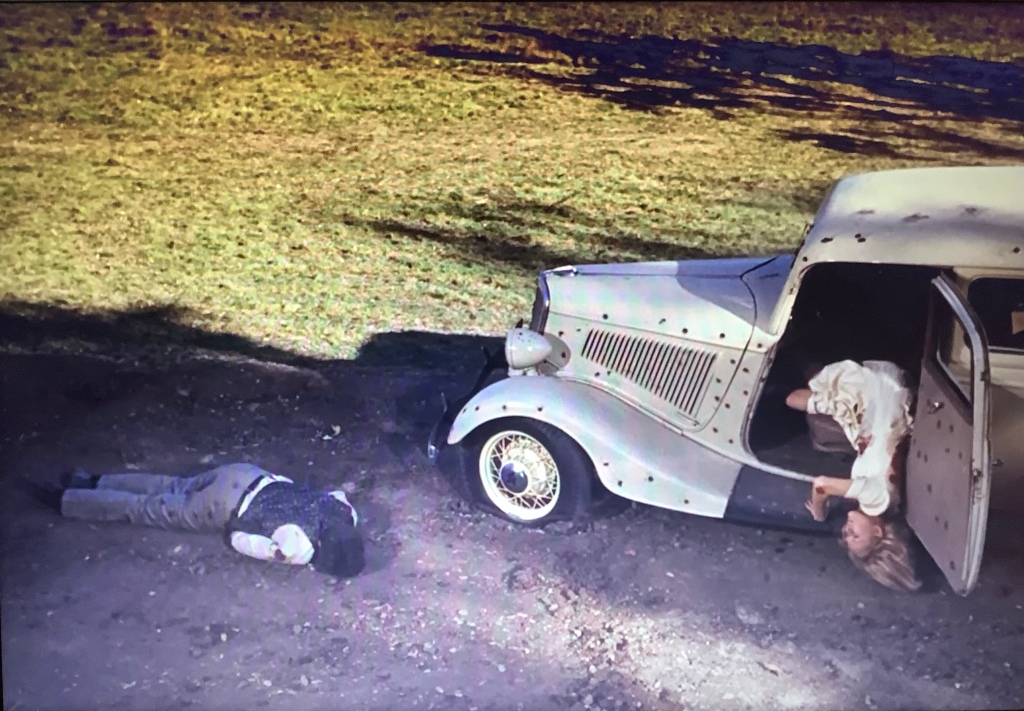

The montage in which Combo’s gang wreaks havoc serves as Shane Meadows’ ultimate indictment of nationalism, racism, and the toxic ideology that is often associated with it. The camerawork is gliding, graceful and carefully framed, as seen in previous montages earlier in the film. This creates a sense of unease and discomfort for the audience, as the viewer is forced to confront to the racist hate crimes head-on. Throughout the sequence, the skinheads are simultaneously portrayed as threatening and pathetic. In large numbers, the group are a force to be reckoned with, displayed through the claustrophobic two-shot of Combo and the boy playing football. However, they are individually pathetic and dim witted, as evidenced by the wide shot showcasing misspelled racist graffiti. This technique serves to undermine the group’s power and authority, reinforcing the film’s anti-nationalist ideology. Meadows also depicts the indoctrination of Shaun, as he is taught racist phrases and is trained in the ways of racist hate crime. This is perhaps best underpinned through the superimposition of Shaun walking through a tunnel, overlayed with racist graffiti. In effect, this sequence serves to subject the audience to the repugnance of racism and the danger of extremist ideologies.

Towards the end of the film is a montage that mirrors the opening montage made up of newsreel footage – this serves as a bookend for the film, encouraging the audience to question the dangers of nationalism. The montage acts as an implicit commentary on the dangers of patriotism, exemplified through footage which displays a solider erecting a British flag in a tiny village. This encourages the viewer to question the validity of the British victory during the Falklands War, which directly impacted upon Shaun’s life. This showcase of the grim reality of working-class life in England reinforces the dangers of blindly following nationalist ideologies. This message is further emphasised during the final scene of the film, displaying Shaun throwing the English flag into the water, symbolising his ultimate rejection of a nationalist ideology. The final shot of the film is a closeup of Shaun looking directly into the camera, breaking the fourth wall. This underpins Meadows’ ideological messaging – the film’s anti-nationalist agenda is not up for interpretation or debate.

In conclusion, viewing Trainspotting through the lens of an ideological critical approach reveals the film’s attempt to comically deconstruct the messages that are typically conveyed to the youth. Despite the film’s ideological ambiguity, taking this particular approach has been useful in unravelling the thematic substance of the film. Conversely, employing an ideological critical approach for This is England allows for the film’s unashamed anti-nationalist ideology to be fully comprehended, encouraging us to question the nationalism and indoctrination that pervaded England during the 1980s.

You must be logged in to post a comment.