Overview

The “meeting family” sequence of Bonnie and Clyde (Arthur Penn, 1967) begins after Bonnie runs away from the gang into a field, after which Clyde desperately attempts to locate her as he repeatedly calls her name. After he finds Bonnie, she informs Clyde that she wishes to see her mother again. We then cut to a barren wheat field in which the members of the gang, now made up of: Bonnie, Clyde, Buck, Blanche, and C.W. convene with Bonnie’s family, in order to partake in a family gathering. This desolate location is highly symbolic, perhaps foreshadowing Bonnie and Clyde’s inevitable demise. To accentuate this, this sequence is filmed in a manner reminiscent of a dream sequence – providing the setting with an otherworldly quality. The sequence ends with Clyde’s boyish charm failing to convince Bonnie’s mother that everything is okay, as she tells him that “you best keep running, Clyde Barrow”.

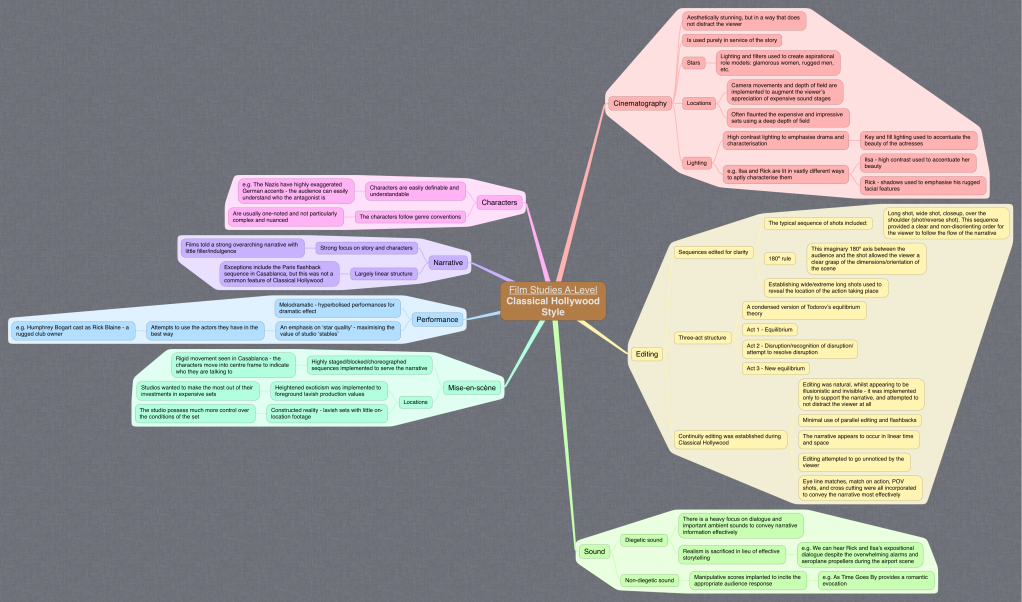

Key Elements, Context, and Representation

The opening scene in which the gang attempt to locate Bonnie is a prime exemplar of the how the film takes dual influence from the familiar Classical Hollywood style alongside newer, more experimental influences such as the French New Wave. As for the Classical Hollywood style, the camera is placed on a rig to seamlessly track the car’s movements as the camera moves backwards. The use of a rig creates a highly controlled environment, typical of films such as Casablanca (Michael Curtiz, 1942). The use of a crane shot is also employed to display Clyde chasing Bonnie through the field, a technique also frequently implemented throughout the films of the Golden Age. Techniques that are inspired by the French New Wave includes the use of long lenses to film. This, alongside improvised handheld camera movements and blocking when Clyde chases Bonnie through the wheat field, creates a naturalistic atmosphere. The scene is also shot on location, meaning that the visuals are not particularly clear. However, this only serves to add an extra layer of realism to the scene.

The weather also appears to break continuity during certain shots – the wheat field appears to be in shadow until it cuts to a closer angle, displaying a much sunnier scene. A piece of wheat also flaps in front of the camera, demonstrating the uncontrollable nature of filming on location. The fact that the couple lie in a dead wheat field is perhaps an example of metaphorical foreshadowing – Bonnie and Clyde’s demise is inevitable.

After Clyde agrees to the family gathering, we then cross-dissolve to a new location, the abandoned industrial wasteland. The sequence opens on a wide shot of this wasteland, displaying the moribund state it exists after the Great Depression. During the scenes that take place in this setting, a grainy filter is applied to the camera that was achieved by filming through a car windscreen. This creates a distant, otherworldly atmosphere to the scene, implying that these brief moments of happiness only prolong the couple’s inexorable downfall. The colouring also appears to be extremely washed out, further emphasising the barren atmosphere that the family are forced to seclude themselves within.

The closeup of Bonnie’s mother is also shot on a long lens, creating an entirely shallow depth of field behind her. This serves to separate her face from the background, drawing the viewer’s attention towards her withered appearance. Each character is also dressed in solemn, formal clothing – reminiscent of funeral attire, contributing the overall ‘death metaphor’ present throughout the sequence. The sound throughout the sequence also appears to be much more distant than normal, merely consisting of muffled diegetic ambience and dialogue. The use of frame rate drops are also employed, jarring the viewer and creating a disjointed atmosphere.

As Bonnie and Clyde innocently play with Bonnie’s nephew in the pit, Buck and Blanche awkwardly stand to the side in a subdued manner. From this, the viewer is able to surmise that Buck and Blanche have realised the inevitably of Bonnie and Clyde’s demise and are empathising with the couple’s blissful naïveté. Clyde’s charismatic charm doesn’t appear to convince Bonnie’s mother of his suitability as a partner for her daughter. During this, Bonnie is portrayed in a much less playful and flirtatious light – she takes on a solemn demeanour, displaying concern for her future with Clyde. As Bonnie’s mother delivers her truthful opinion of Clyde to his face, she is once again isolated in a closeup – emphasising that no one possesses any hope for their future.

As the characters slowly begin to leave the frame, the final conversations revert back to utilising a typical shot/reverse shot sequence. This reinforces the idea that the jovial family gathering has now concluded, and the gritty reality of the poverty-struck South has once again become apparent. The sequence ends with a wide shot of the abandoned wasteland, leaving the Barrow Gang isolated in the frame – informing us that the family does not intend to aid their efforts, and the gang is truly alone.

You must be logged in to post a comment.