Bonnie and Clyde (Arthur Penn, 1967) could arguably be considered a film influenced by an array of creative auteurs and external inspirations, rather than a product created under the vision of a singular auteur. Including the prolific young directors of the French New Wave movement, the director of the film Arthur Penn, editor Dede Allen, and producer/star Warren Beatty, the final state Bonnie and Clyde exists as such due to the collaborative influence of these distant yet imperatively necessary auteurs.

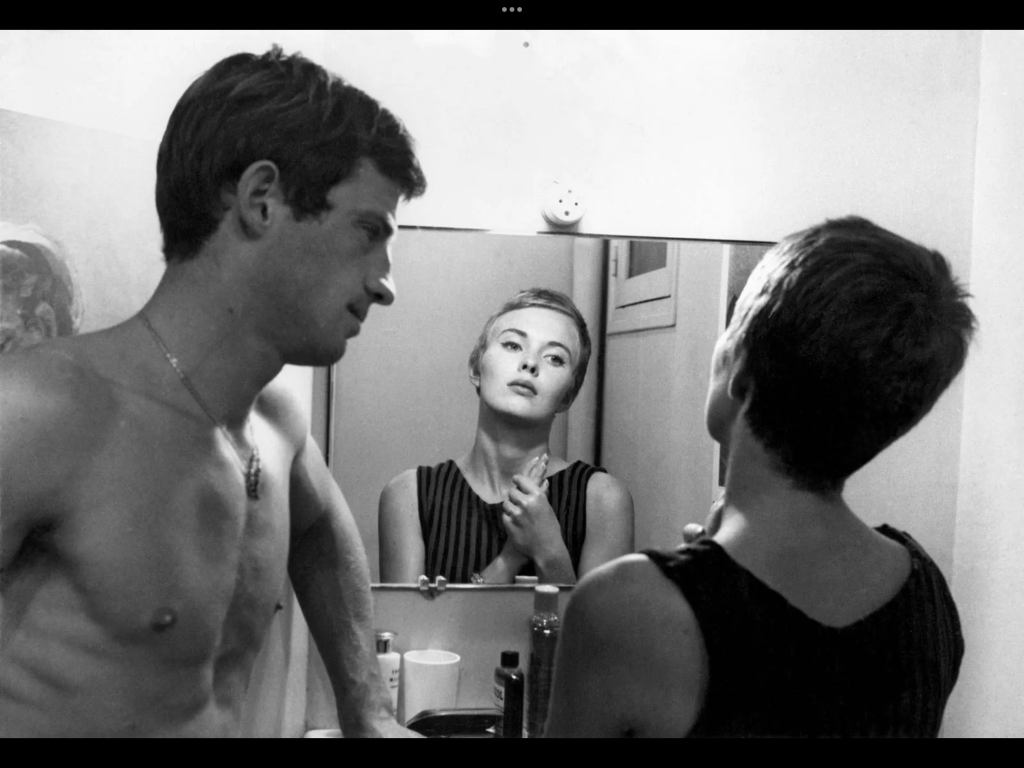

Although the film was produced by Hollywood studio Warner Brothers, Bonnie and Clyde took a great deal of influence from the French New Wave. This movement is characterised by its particular focus on young, eccentric characters living in a poverty-stricken corner of society. Directors of the French New Wave often used handheld cameras to film in an improvisational and fluid style, in tandem with jump cuts to create a naturalistic and authentic atmosphere within their films.

The film’s director, Arthur Penn was highly influenced by this style of filmmaking, imbuing Bonnie and Clyde with many of these techniques. A clear example of this can be seen in the opening scene of the film, which displays Bonnie getting ready in her room, during which a handheld camera follows her movements spontaneously and fluidly. Bonnie’s entrapped state of mind is aptly conveyed when she is claustrophobically framed within her bed-frame. Penn also chose to shoot the vast majority of the film on location with natural lighting, only contributing to the film’s purported authenticity.

Dede Allen, a celebrated ‘auteur editor’ within Hollywood, also had a significant impact upon the film’s production. During her career, she pioneered the use of audio overlaps and jump cuts to create a sense of driving energy, and this can be clearly observed throughout Bonnie and Clyde. Allen also incorporated the technique of temporally disruptive editing throughout the film. In the opening sequence for example, Allen subtly conveys the passage of time through jump cuts whilst maintaining a fluid movement, only adding to the naturalistic tone of the film.

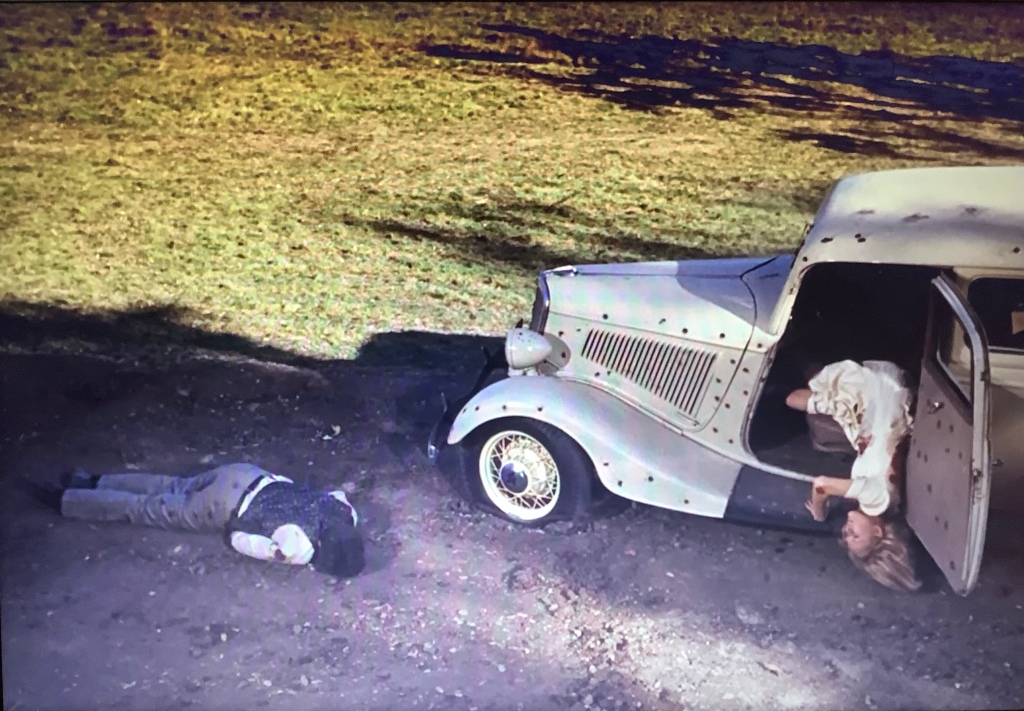

Bonnie and Clyde was produced by Warren Beatty, who also stars as Clyde in the film. Beatty was responsible for assembling most of the cast, alongside selecting Arthur Penn to direct the film, with Beatty choosing to give Penn 10% of the film’s profits. Beatty was arguably the driving force behind the film, overseeing each element of production. Beatty also spearheaded the film’s gritty and realistic portrayal of Bonnie and Clyde’s escapades – he insisted that the film would not shy away from portraying the duo as flawed and multi-faceted individuals. Beatty also decided to create an air of ambiguity concerning Clyde’s sexuality. All of this served to reject the traditional conventions of the Classical Hollywood Style, marking its place in film history as the trailblazing film of the New Hollywood era.

You must be logged in to post a comment.