Compare how far your chosen films reflect their different production contexts.

Sample Assessment Materials

Plan:

Introduction

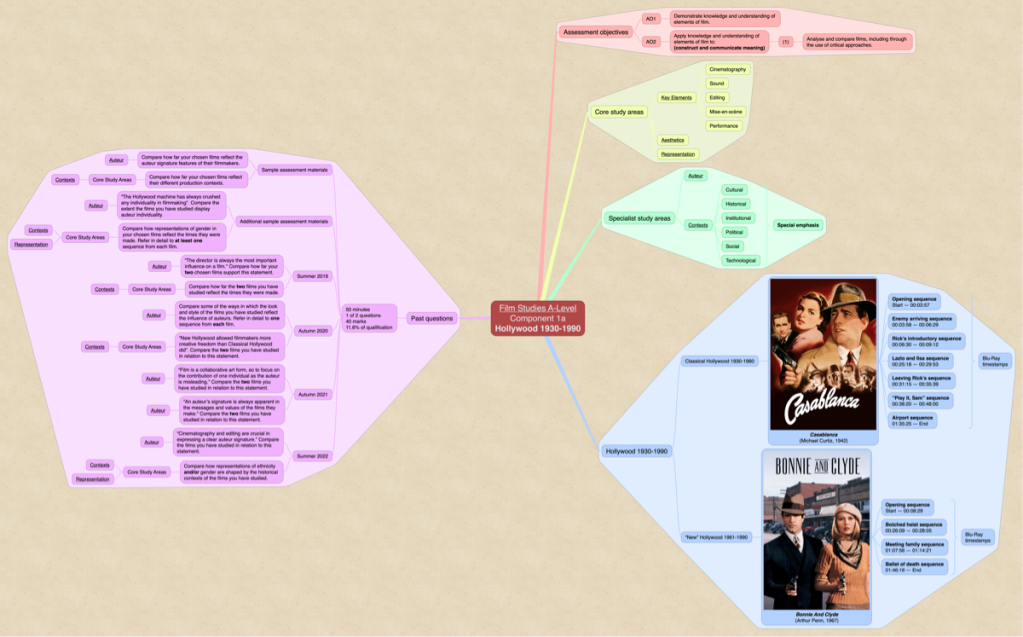

Casablanca (Michael Curtiz, 1942) and Bonnie and Clyde (Arthur Penn, 1967) are two films that are shining exemplars of two starkly contrasting production contexts within Hollywood. Casablanca was a film produced by Warner Brothers under the Hollywood Studio System during the Golden Age – one which epitomises the rigid and traditional Classical Hollywood style of the era. Conversely, Bonnie and Clyde sought to defy the preconceptions of the Golden Age after the dissolution of the studio system, taking influence from the French New Wave to employ modern technology and unorthodox filmmaking techniques. The film foregrounds a gritty portrayal of two real life criminals – one which does not shy away from graphic violence and sexual undertones – birthing the New Hollywood era of filmmaking.

Body

Institutional context: Compare how Casablanca was produced by Warner Bros under the studio system (vertical integration, unbreakable contracts, star system, Hays code etc.). Whereas Bonnie and Clyde was produced after the Paramount Case, allowing for a greater deal of creative freedom within Warner Bros.

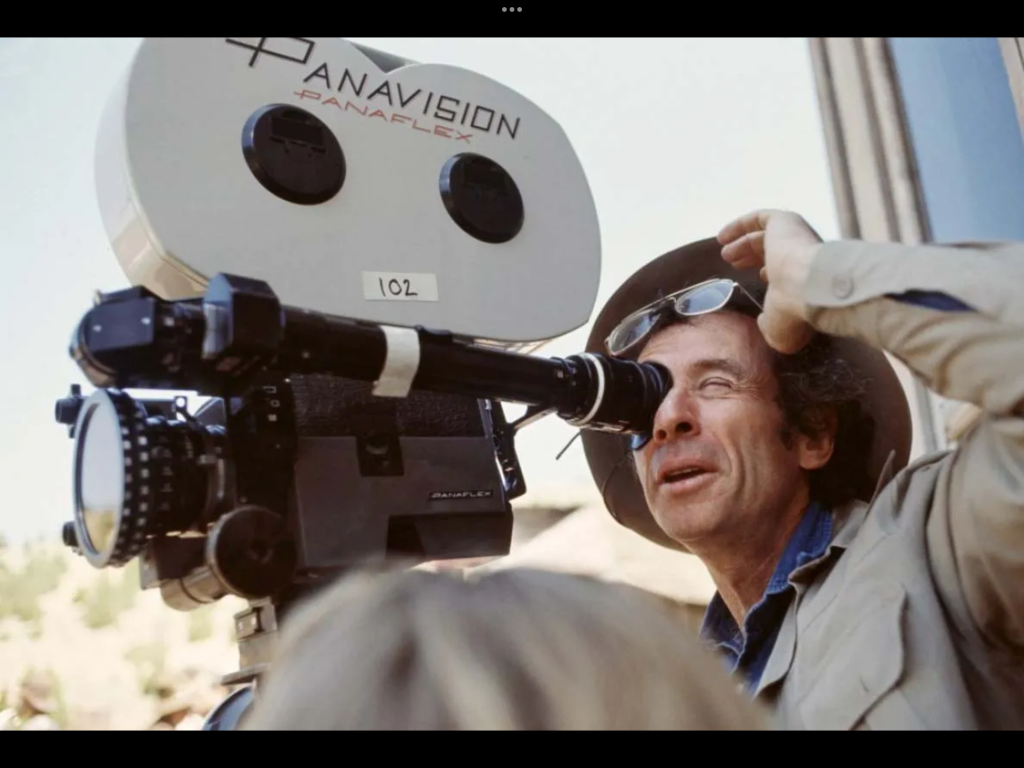

Technological context: Compare the styles of filmmaking (Classical Hollywood style vs French New Wave-influenced style). Mention specific examples rooted in key sequences, alongside the technology available to the studios. Filmed in the studio vs on-location.

Historical context: Compare how Casablanca was filmed and set during the First World War (Vichy water implications), but Bonnie and Clyde is set in a Great Depression 1930s (FDR posters plastered on the wall) , but released during the 1960s.

Comparing how the film stars are presented: Casablanca (Ilsa is glamorous and pristine, through key and fill lighting, Rick’s rugged appearance accentuated by lighting).

Conclusion

Ultimately, both films are apt representations of the production contexts that both films were produced under respectively. Casablanca epitomises the Classical Hollywood style typical of the films of the Golden Age, whereas Bonnie and Clyde paved the way for the New Hollywood era – embracing graphic violence and sexual content that defied the typicalities of the more traditional, conservative films of the previous age.

Essay – Version 1

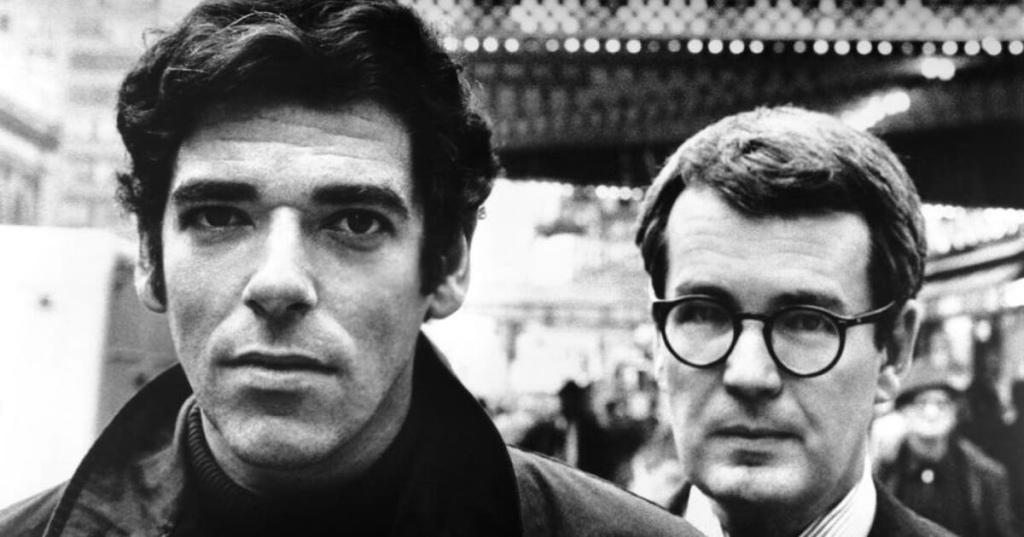

Casablanca (Michael Curtiz, 1942) and Bonnie and Clyde (Arthur Penn, 1967) are two films that are shining exemplars of two starkly contrasting production contexts within Hollywood. Casablanca was a film produced by Warner Brothers under the Hollywood Studio System that operated under the practice of vertical integration during the Golden Age. The film epitomises the rigid and traditional Classical Hollywood style of the era. Conversely, Bonnie and Clyde sought to defy the preconceptions of the Golden Age after the dissolution of the studio system. By taking influence from the French New Wave, employing modern technology and unorthodox filmmaking techniques, this appealed to the newly diverse cinematic landscape enjoyed by audiences throughout this period. The film foregrounds a gritty portrayal of two real life criminals – one which does not shy away from graphic violence and sexual undertones – birthing the New Hollywood era of filmmaking.

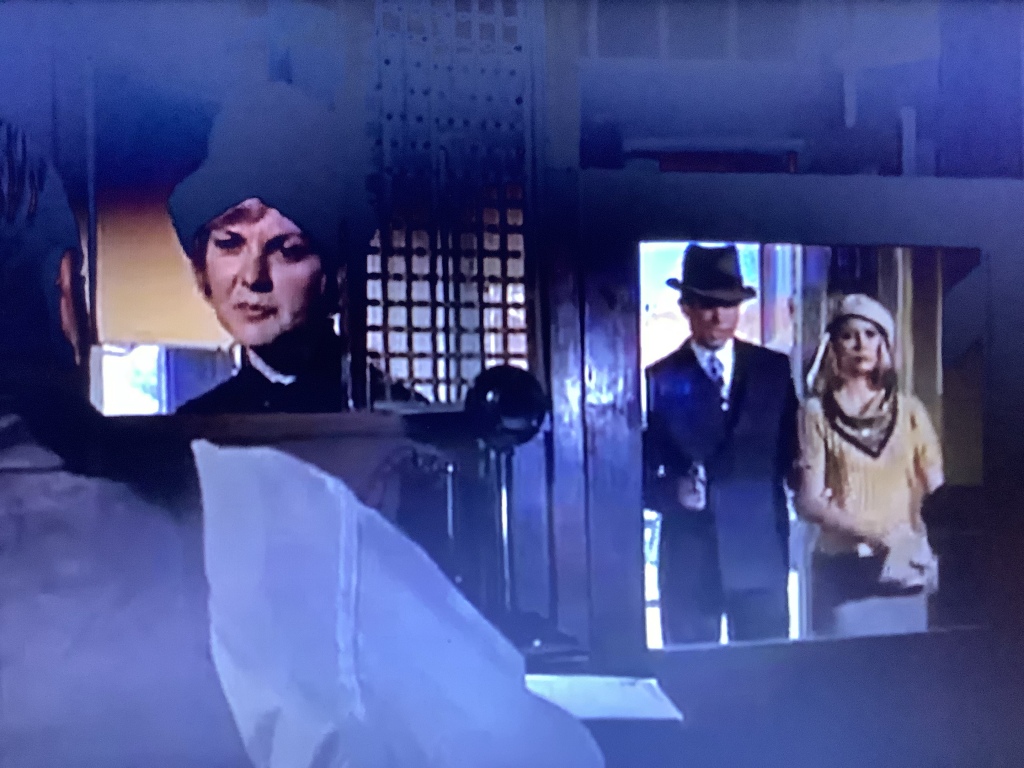

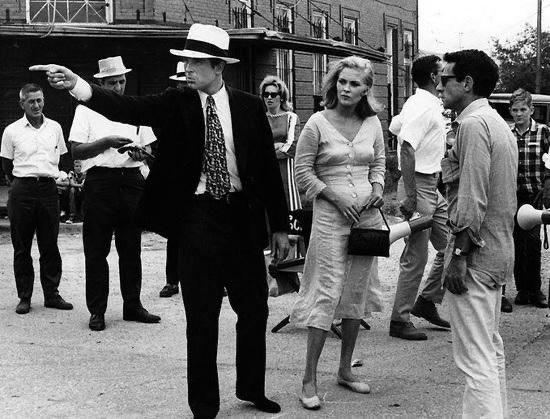

Casablanca’s conception originated with Warner Bros. buying the rights to a unproduced stage play, Everybody Comes to Rick’s, for $20,000. Afterwards, the studio quickly began work on building bespoke sets for the film, creating the illusion of exoticism by foregrounding the lavish production values that the studio poured into the construction. A clear example of this can be seen in the opening sequence of the film in which an expansively lavish set of Casablanca populated with countless extras takes place. This is revealed to the viewer through camerawork typical of the Classical Hollywood style: a crane shot that tilts down to reveal the opulent set. Conversely, Bonnie and Clyde strove to purport the highest level of authenticity and thus, chose to film the vast majority of the film on location with the implementation of natural lighting. The opening sequence of the film introduces us to Clyde through a wide shot filmed through a mosquito net, creating an atmosphere that feels much more tangible than Casablanca’s constructed reality. Akin to the French New Wave, the use of natural lighting serves to add an extra layer of authenticity to the film.

Casablanca is a product of the Golden Age of Hollywood that exemplifies the concept of film star ‘stables’ that were owned by the studios. Due to ‘unbreakable contracts’ that exclusively contracted actors to specific studios, Warner Bros. endeavoured to make apt use of their stars. With this in mind, the studio chose to cast Humphrey Bogart as Rick, a star who was often typecast as the ‘rugged individual’ archetype in films such as The Maltese Falcon (John Huston, 1941). Through this, Rick’s character was customised to suit Bogart’s acting capabilities, introducing us to him in the ‘Leaving Rick’s’ sequence by filming Bogart from a centrally framed low-angle shot whilst being cast in shadow to accentuate his masculinity. In addition to this, during the Paris flashback sequence, Rick dons a trench coat and hat during the train station scene. This subtly pays homage to Humphrey Bogart’s classic detective roles he was cast as during the Film Noir scene, demonstrating that Warner Bros. attempted to fully capitalise on the ‘stable’ of stars they possessed. The studio also chose Ingrid Bergman to play Ilsa, an internationally renowned actress. Throughout the film, Bergman was highly glamourised through the use of lavish costume design, hair, makeup, alongside the use of key lighting and soft focus to accentuate her beauty. This is highly typical of the Classical Hollywood style that Warner Bros. was renowned for at the time.

In contrast, the titular couple in Bonnie and Clyde are presented in a vastly different light. Instead of conforming to the ‘rugged individual’ protagonist archetype, Clyde is presented in a much more nuanced manner due to his ambiguous sexuality that Warren Beatty (producer and star) campaigned for. Towards the end of the opening sequence of the film, a closeup is displayed of Clyde drinking a bottle of Coke, which both connotes provocatively phallic imagery and is indicative of the Prohibition Era that was in effect during the 1930s. This is furthered later in the film when Clyde appears to be uninterested or perhaps unable to engage in sexual activity with Bonnie. Bonnie is presented in a much more seductive manner in contrast to Ilsa, which is immediately demonstrated to the audience through the first shot of the film – an extreme closeup of her luscious red lips, a symbol of sex. This, alongside the fact that Bonnie appears naked for the first scene of the film, presents her feminine beauty in a more natural and intimate manner than Ilsa’s artificially maintained beauty.

Casablanca’s production was spearheaded by Jack L. Warner – the president of Warner Brothers. A primary agenda of Warner was to feature the ongoing war prominently in the studio’s films, in an attempt to subtly signal America to join the war efforts. This is particularly evident in the final scene of the film, in which Captain Renault chooses to bin the Vichy-branded water bottle, displayed to the viewer through a closeup. This is symbolic of the studio’s negative views towards fascism, perhaps being indicative of the side the country eventually took when America joined the war. Historical context is also important to consider when evaluating the production contexts of Bonnie and Clyde. Although the film was released in 1967, it is set during the 1930s – a time in which the effects of the Great Depression coursed through all of America, particularly the poorer Southern states in which the film takes place. For example, the streets that the couple walk down in the opening sequence are barren, reflective of the Great Depression. The mise-en-scène is also meticulously selected to reflect the time period, such as the FDR presidential campaign posters that are plastered to the walls, serving to immerse the audience in the 1930s. Through this, viewers who had lived through this time period themselves were encouraged to empathise with Bonnie and Clyde’s struggles during this period of poverty and bleakness.

Casablanca was shot entirely in black and white, a typical feature of Warner Brothers’ ‘house style’ at the time. By 1942, colour had been implemented into a number films for around a decade, with studios such as MGM immediately choosing to embrace colour. MGM would go on to produce The Wizard of Oz (Victor Fleming, 1939) a landmark of the cutting-edge Technicolor technology, but colour was considered by many other studios to merely be a ‘gimmick’. During the time of Casablanca’s release, black and white was arguably at its peak, and Warner Bros. believed that choosing to film in black and white – despite the introduction of colour technology – demonstrated artistic nuance, as the iconic ‘noir aesthetic’ had now been refined for over 50 years. Colour was not as ‘sterile’ as black and white was during this time, only being able to display highly saturated colours. Conversely, Bonnie and Clyde was shot in colour, aptly portraying a much grittier and authentic atmosphere in contrast to Casablanca romanticised ‘noir’ aesthetic. The film’s cinematographer, Burnett Guffey, once stated that Arthur Penn wanted the film to be “as real and untheatrical as possible” and the decision to embrace modern Technicolor technology supports this.

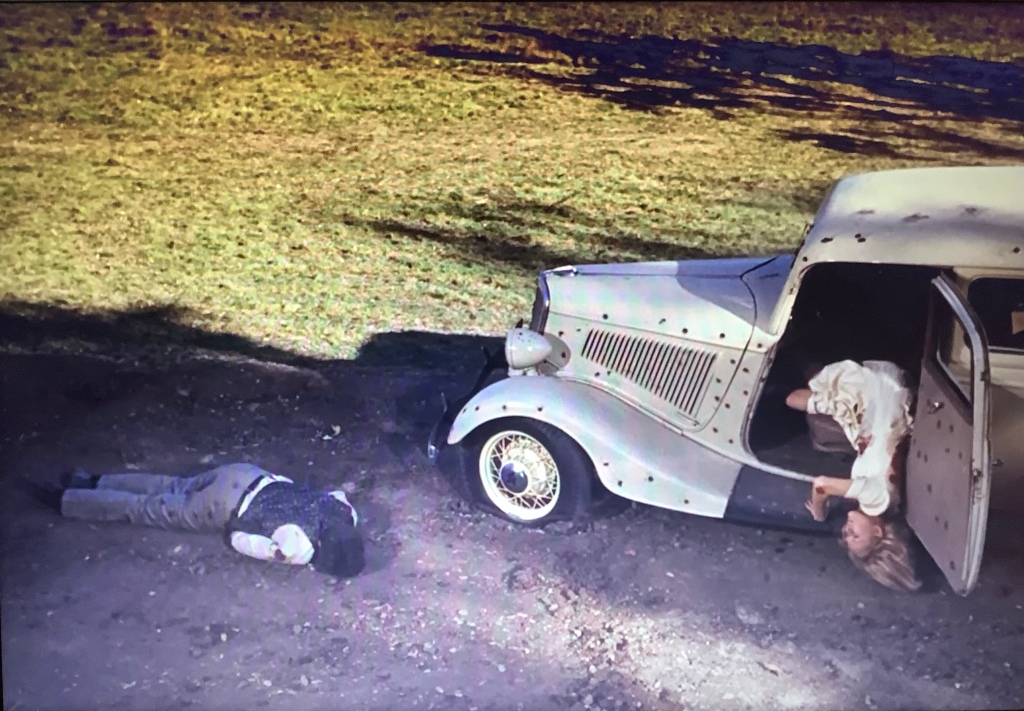

During the production of Casablanca, the studio was significantly limited by the Hays Code – a series of regulations that forbade graphic violence and sexual content to be displayed within the film. This is particularly evident in the final scene of the film in which Rick shoots Major Strasser, after which no blood is shown, indicative of the Hays Code restrictions. This conservative presentation of violence soon became a typical convention of the Classical Hollywood style, to which audiences became accustomed during the Golden Age. This greatly contrasts with how violence is presented throughout Bonnie and Clyde. After the dissolution of the studio system that occurred after the result of the Paramount Case, the Hays Code gradually became more lax over time, resulting in Bonnie and Clyde’s presentation of graphic violence as a means to shock audiences who had become accustomed to the conservative presentation of violence typical of Classical Hollywood. At the end of the ‘Botched Heist’ sequence, Clyde shoots a man in the mouth through a car window. This is presented to the viewer through rapid editing, cutting quickly between closeups of the man clinging to the car and reactionary shots of Clyde. The film does not shy away from its presentation of blood, with the film implementing the use of squibs filled with stage blood, which exploded upon impact. These were employed in this scene, alongside many others throughout the film, including the infamous massacre of the titular couple at the end of the film. This graphic display of violence serves to ground the film in reality and forces the audience to confront Bonnie and Clyde’s heinous actions.

Ultimately, both films are apt representations of the production contexts that both films were produced under respectively. Casablanca epitomises the Classical Hollywood style typical of the films of the Golden Age, whereas Bonnie and Clyde paved the way for the New Hollywood era – embracing graphic violence and sexual content that defied the typicalities of the more traditional, conservative films of the previous age.

You must be logged in to post a comment.