How valuable has ideological analysis been in developing your understanding of the themes of your chosen films?

Sample Assessment Materials

Plan:

Introduction

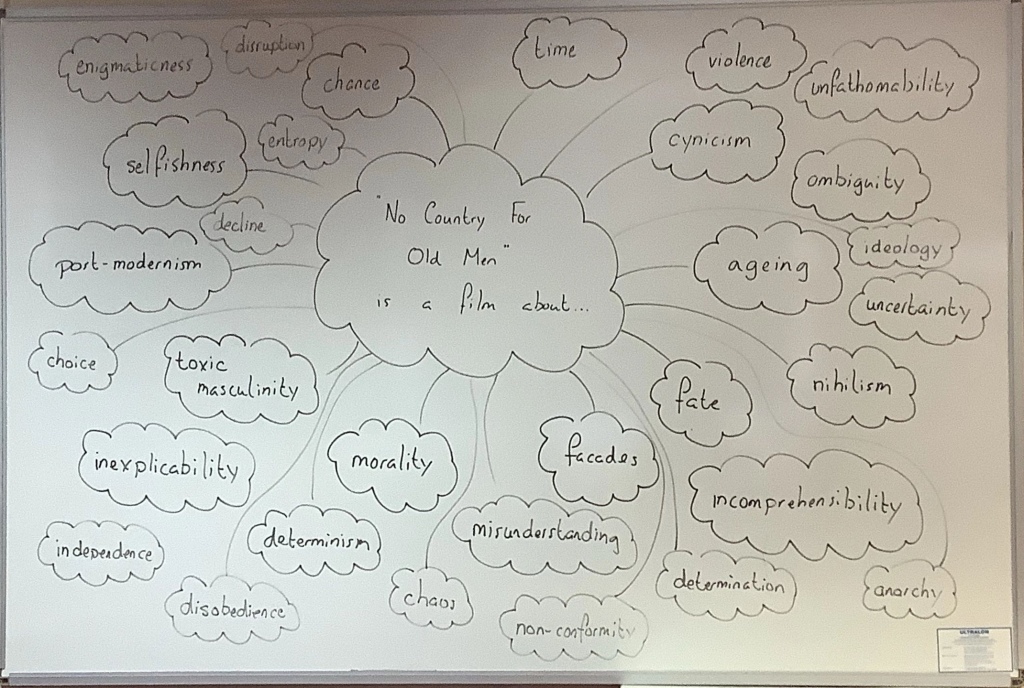

Ideological analysis is a critical viewpoint that has served to be invaluable in the thematic comprehension of both Winter’s Bone (Debra Granik, 2010) and No Country For Old Men (Joel and Ethan Coen, 2007). Viewing Winter’s Bone through the lens of a feminist ideology allows for the examination of how women are oppressed within a male-dominated patriarchy. A feminist lens reveals the film’s implicit messages concerning gender, and how it affects social power dynamics. Conversely, viewing No Country For Old Men through a nihilistic ideological viewpoint has allowed for a broader understanding of its enigmatic themes presented over the course of the film. The film’s antagonist, Anton Chigurh, is the film’s primary embodiment of nihilism – he rejects traditional morals and is instead driven by the meaninglessness of human existence.

Body

Winter’s Bone – feminist ideological analysis is the best approach

- Ree’s competence – attending to maternal and paternal duties (chopping wood and cooking)

- Bechdel test, male gaze, non-sexualising clothing

- Androgynous children appearances – Ashlee wishes to hunt, Sonny is squeamish

- Poverty expressed through mise-en-scène

- Ree’s interactions with men – Teardrop, sheriff, Thump Milton, etc.

- Overwhelming male domination of cattle market – incomprehensible dialogue. Sickening yellow palette, steely blue palette of herding location

- Squirrel dream sequence – 4:3, grainy handheld footage, dreamy. Chainsaw symbolic representation of the patriarchy, squirrel is the oppressed women

- Narrative resolution solved through female discussion and cooperation

No Country For Old Men – nihilistic ideological approach

- Barren landscapes of Texas reflect nihilism

- Ed Tom monologue at start. Ed Tom and Ellis dialogue about senseless violence

- Anton’s brutal murders. Leaving victims’ fates up to a coin flip. Petrol station owner and Carla Jean

- Llewelyn – no empathy towards man begging for water. Takes money briefcase McGuffin, nihilist causality. Sudden offscreen death.

- Ed Tom dreams

Conclusion

Ultimately, the meanings of both Winter’s Bone and No Country For Old Men are vastly enriched when taking particular ideological analysis into account. Viewing Winter’s Bone through a feminist lens allows for an astute appreciation of Granik’s implicit “feminist film about an anti-feminist world”. Taking the ideological viewpoint of nihilism for No Country For Old Men, on the other hand, enables the Coen Brothers’ ambiguous thematic substance to be unravelled, ultimately resulting in a deeper appreciation of the film.

Essay – Version 1

Ideological analysis is a critical viewpoint that has served to be invaluable in the thematic comprehension of both Winter’s Bone (Debra Granik, 2010) and No Country For Old Men (Joel and Ethan Coen, 2007). Viewing Winter’s Bone through the lens of a feminist ideology allows for the examination of how women are oppressed within a male-dominated patriarchy. A feminist lens reveals the film’s implicit messages concerning gender, and how it affects social power dynamics. Conversely, viewing No Country For Old Men through a nihilistic ideological viewpoint has allowed for a broader understanding of its enigmatic themes presented over the course of the film. The film’s antagonist, Anton Chigurh, is the film’s primary embodiment of nihilism – he rejects traditional morals and is instead driven by the meaninglessness of human existence.

When choosing to view the opening sequence of Winter’s Bone through the lens of a feminist ideology, a critical framework rooted in analysing how women are oppressed throughout film, it becomes clear that the protagonist, Ree, is a symbol of feminism and female empowerment. She competently attends to an array of domestic tasks throughout the sequence, such as chopping wood and cooking. This indicates that Ree does not conform to typical gender roles typically presented throughout the Hollywood landscape, performing duties that are stereotypically considered both maternal and paternal. This is accentuated through Ree’s baggy non-gendered clothing – she is not sexualised in any way throughout the film, nonconforming to the ‘male gaze’ that permeates Hollywood.

Similarly, Ree’s siblings Ashlee and Sonny have notably androgynous appearances, implying that gender does not factor into how these children are to be nurtured by Ree. In fact, Granik actively subverts gender stereotypes during the ‘squirrel gutting’ sequence, during which Ashlee displays a desire to hunt animals, whereas Sonny appears to be much more squeamish and reluctant. This subtle subversion of gender stereotypes serves to reinforce the feminist ideology that the film adheres to, deepening the understanding that can be extracted from it. An interesting role reversal also occurs when Ree combs her mother’s hair later in the sequence, a typical action performed by a mother to her daughter. This emphasises the multi-faceted familial duties that Ree is burdened with attending to. The film also passes the Bechdel test numerous times during the opening minutes of the film, with the interaction between Ree and Sonja concerning a horse perhaps best exemplifying the feminist ideology conveyed by the film.

Ree can be seen standing her ground against the male characters that attempt to hinder her goals, such as the sheriff in the opening sequence who informs her that her house is to be sold for her father’s bond. She addresses the sheriff with confident remarks such as “I’ll find him”, highlighting the difficulty she faces within an oppressive, patriarchal society. Ree displays a similar level of defiance and empowerment towards her uncle Teardrop, who represents the oppressive toxic masculinity that pervades the Ozarks. A focus pull is implemented to draw our attention towards him as he edges closer to Ree. Teardrop’s appearance is notably scruffy and ragged, displaying the impoverished state of the Ozarks. A simple shot/reverse shot sequence is employed throughout this scene, as opposed to a low/high angle shot alternation. This indicates that the power dynamic between Ree and Teardrop is equal, aligning with the feminist ideology the film adheres to. After Teardrop informs Ree of Jessop’s car being burned, her expression remains stoic, emphasising Ree’s resilience she has garnered after becoming the family’s primary caregiver.

During the ‘cattle market’ sequence, the oppressive patriarchy is symbolically conveyed through the use of an overwhelming soundscape. The diegetic sound of the unintelligible language of the auction dominates the sound mix, serving to reinforce the idea that the masculine world is incomprehensible to Ree, emphasising the power dynamic between her and the men. The cow at the center of the scene appears frightened, its life dependent on the mercy of the men, further reinforcing the domineering force that the men exert. The men are also all white and middle aged, reinforcing the homogenous patriarchal hive mind the men represent.

A standout sequence of Winter’s Bone is the ‘squirrel dream’ sequence, during which Granik employs unorthodox filmmaking techniques to reinforce the female oppression presented throughout the film. Using a cheap handheld camera, black and white, alongside a 4:3 aspect ratio to create an otherworldly atmosphere, the squirrel in the sequence is a perhaps a metaphorical embodiment of Ree, with both being victims of a disrupted equilibrium. The danger faced by the squirrel is displayed through its shuddering fear, captured through the camera’s rapid and disorienting movements. A jarring diegetic chainsaw sound promptly enters the mix, perhaps being representative of the oppressive patriarchy that endangers Ree’s peaceful existence. A worms-eye-view shot of the trees is used, displaying the squirrel, and by extension, Ree, as dwarfed, emphasizing her vulnerability within an oppressive patriarchal society – a notion that can only be extracted when viewing the film through a feminist ideology.

Although No Country For Old Men could be viewed through a feminist ideological lens, it would perhaps be more insightful to analyse the film through the ideological viewpoint of nihilism. This involves considering the viewpoint that denies the existence of any inherent meaning or value in human life, instead emphasising the absurdity of existence.

The film’s opening sequence begins with a series of bleak yet breathtaking aerial wide shots of the landscape of West Texas. These barren shots serve to establish the inexplicability and meaninglessness of humanity, conveyed through the implied absence of human activity alongside the desolation of the terrain. The landscape is stark and unforgiving, with no signs of life or hope, reinforcing the film’s nihilistic worldview. The imagery is suggestive of the fact that the world is a cold and indifferent place, where human existence is inconsequential.

The opening sequence of the film also introduces the viewer to Llewelyn Moss, the main protagonist. Throughout the sequence, he is often filmed from extreme long shots to reinforce the desolate, unwelcoming landscape. He soon stumbles upon a drug deal gone wrong, after which he remains stoic and unfazed towards the array of dead bodies. Llewelyn also shows no empathy towards the dying man begging for water, implying that he has been desensitised to human suffering – a hallmark of a nihilism. After locating a briefcase full of money, the film’s determinist chain of events are set in motion – Llewelyn’s fate is sealed from the beginning, reinforcing the nihilistic ideology that the film adheres to. Llewelyn’s choice to take the money is indicative of his disregard for traditional morals and societal norms.

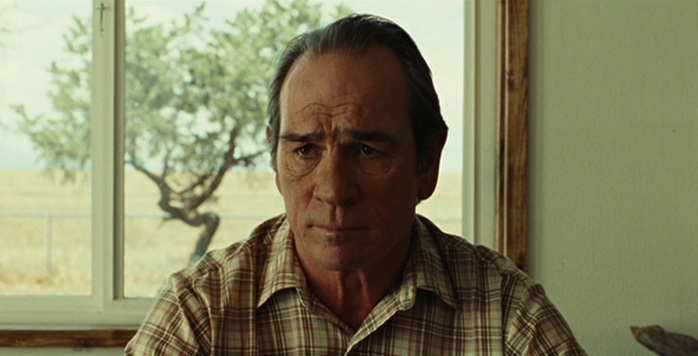

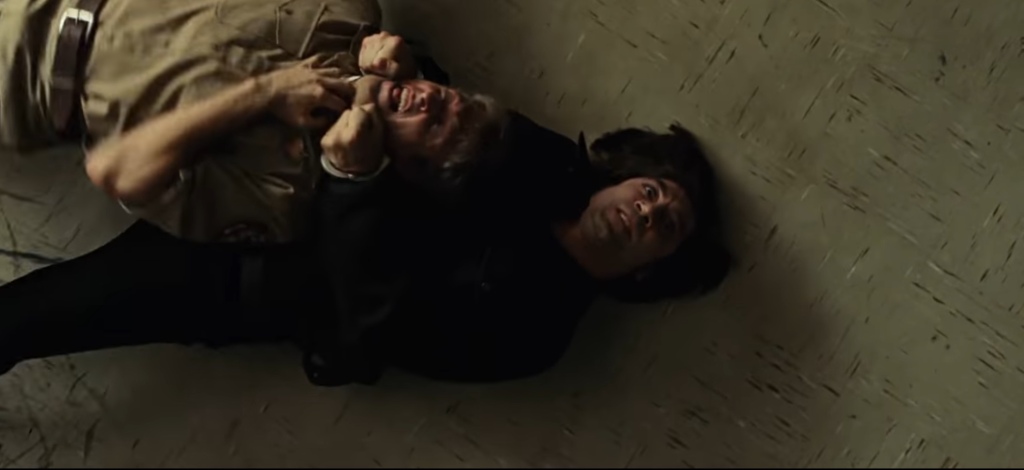

Nihilism is perhaps best exemplified through the character of Anton Chigurh, a ruthless hitman driven purely by his belief in the futility of humanity. In the opening sequence, the viewer is introduced to Anton committing two brutal murders in sequence. The first is using a pair of handcuffs, during which a series of birds-eye-view and mid shots display Anton’s senselessly graphic violence, which emphasises his disregard towards human existence. This also acts in stark juxtaposition to the aforementioned pensive opening scene of the film. The second murder involves Anton duping a truck driver into believing he is a policeman before killing him with a highly unconventional weapon: a cattle gun, suggesting that he views humans as mere animals whose existence is futile. He displays no remorse towards extinguishing two human lives in quick succession, reinforcing his character as a symbol of nihilism.

Anton’s flippant attitude towards human existence is perhaps best underpinned by the symbolism that can be inferred through his decision to let his victims decide their fate through a coin flip at multiple points throughout the film. Anton leaves a perfectly innocent man’s fate up to a 50/50 chance, during the ‘call it, friend-o’ sequence, reinforcing his nihilistic belief that human life is meaningless and arbitrary. During the scene, the Coens employ a tight shot/reverse shot sequence throughout, during which the camera gradually pushes in towards the two, further increasing the suspense. After the owner argues that he didn’t put anything up to win on the coin flip, Anton informs the man that “you’ve been putting it up your whole life, you just didn’t know it”, suggesting that the end of the man’s meaningless existence has already been decided.

Sheriff Ed Tom Bell’s opening monologue acts as a perfect introduce to his disillusionment with the nihilism that plagues society. Throughout the monologue, he reminisces upon the senseless crimes that he has dealt with throughout his career, reflecting upon the violence that pervades Texas. He notes that a man who killed a 14-year-old girl told him that “there wasn’t any passion to it” and that “he’d do it again” if they let him out. This serves to reinforce the nihilism towards human existence that dominates the conscience of the region – the sheriff’s disillusionment towards his own traditional beliefs is perhaps reflective of the broader disillusionment that society bears towards the moralistic status quo. The opening monologue sets into motion Ed Tom’s final decision to retire during the film’s closing sequence. A conversation between Ed Tom and his uncle Ellis reveals that the violence stemming from nihilism that permeates the state has ultimately caused Ed Tom to abandon his sense of justice, and retire. When commenting on the violence, Ellis notes that “what you got ain’t nothing new. This country is hard on people. You can’t stop what’s coming”, implying that the atrocities committed by humankind transcend generation, but have instead taken a new form – nihilism. The film’s title even implies that there is no place for “old men” in today’s society – traditional morals are now devoid of any meaning. This analytical viewpoint is indicative of the nuanced meanings that can be extracted from ideological critical analysis.

Ultimately, the meanings of both Winter’s Bone and No Country For Old Men are vastly enriched when taking particular ideological analysis into account. Viewing Winter’s Bone through a feminist lens allows for an astute appreciation of Granik’s implicitly “feminist film about an anti-feminist world”. Taking the ideological viewpoint of nihilism for No Country For Old Men, on the other hand, enables the Coen brothers’ ambiguous thematic substance to be unravelled, ultimately resulting in a deeper appreciation of the film.

You must be logged in to post a comment.