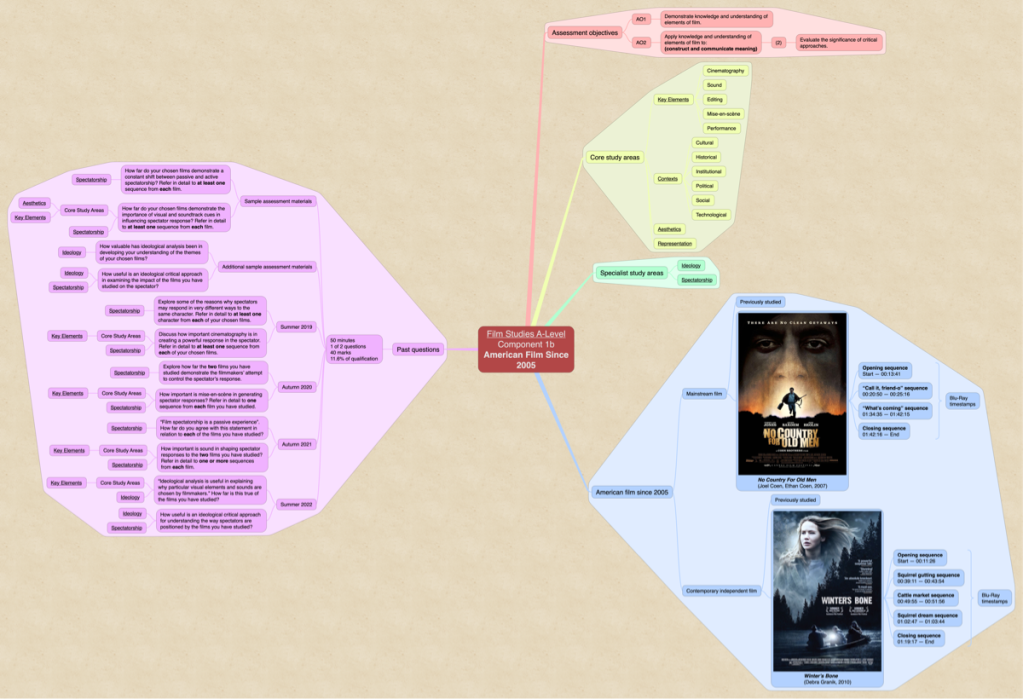

Explore how far the two films you have studied demonstrate the filmmakers’ attempt to control the spectator’s response.

Autumn 2020

Plan:

Introduction

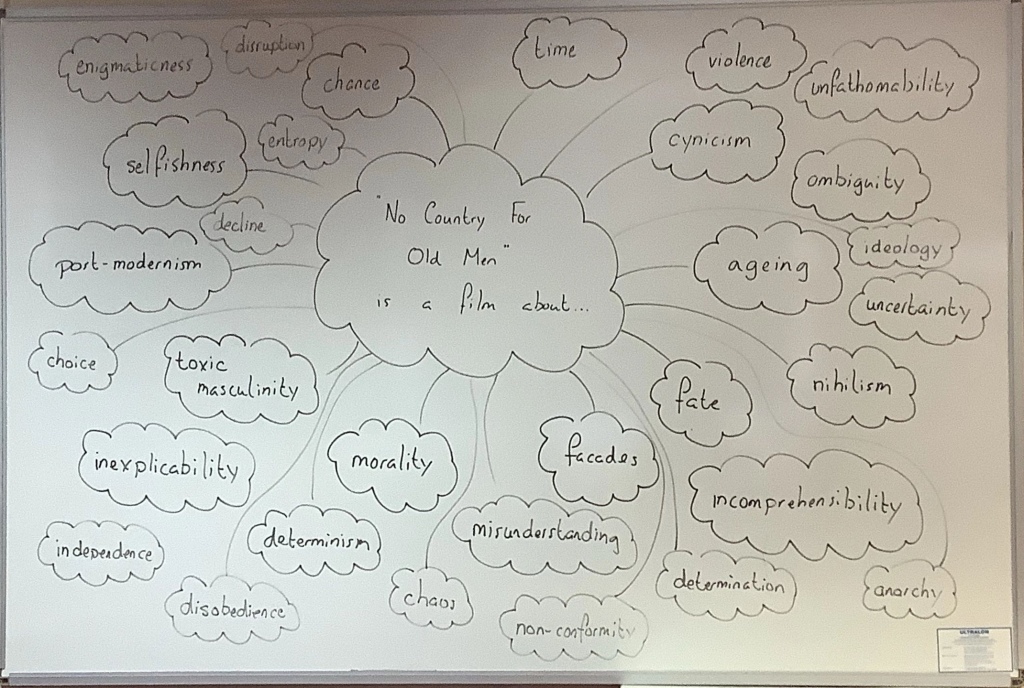

Throughout both Winter’s Bone (Debra Granik, 2010) and No Country For Old Men (Joel and Ethan Coen, 2007), the respective filmmakers persistently attempt to control the spectator’s response in a variety of faceted means. Winter’s Bone implements audience positioning in ways that attempt to elicit empathy within the viewer towards the protagonist, Ree, and her struggles within an oppressive patriarchal society. Granik claims that it is “a feminist film about an anti-feminist world”, implying that the preferred reading is one in which the viewer is encouraged to support Ree’s actions throughout the film. Conversely, the Coen brothers set out to actively subvert the spectator’s preconceptions of narrative in No Country For Old Men, by encoding the film with an ambiguous thematic substance, challenging the spectator’s morals and ideologies. A passive spectator would even perhaps argue that the film is ‘unsatisfying’, as it does not conform to the conventions of a traditional narrative.

Body

Winter’s Bone – incites empathy within the viewer towards the characters, under the context of feminism

- Preferred reading – empathising with Ree as an empowered woman and her struggles against patriarchal oppression

- Negotiated reading – Ree’s actions are still immoral, despite being in a feminist world

- Active spectatorship and negotiated reading during ‘squirrel dream’ sequence. Audience’s own perception will interpret the dream to have a particular meaning – perhaps the squirrel is representative of Ree’s oppression

- Audience is positioned to view Teardrop as a symbol of toxic masculinity

No Country For Old Men – subverting audience’s preconceptions

- No traditional ‘face off’, the Sheriff is mostly uninvolved with the events of the film

- Preferred reading – siding with the Sheriff, sympathy with his disillusionment towards the senseless violence that permeates the state

- Fade to black at the end leaves the audience dwelling upon the sheriff’s dreams – symbolism of following his father into the grave

- Inevitable frustration towards the ‘unsatisfying’ conclusion – Llewelyn’s off-screen death

- Active spectatorship – pensive opening sequence, little to no dialogue. Introspective sheriff monologue – doesn’t drive the plot forward. Exemplifies the rejection of the hypodermic needle theory.

- The preconception of unconditionally supporting the protagonist’s actions is subverted when Llewelyn doesn’t give the man any water and instead takes the briefcase

- The motivations behind Anton’s ambiguous murders are to be inferred by the audience through active spectatorship – checking boots for blood after inferably killing Carla Jean, nihilistic coin flips

Conclusion

In conclusion, Winter’s Bone and No Country For Old Men use starkly contrasting methods in order to control the viewer’s response. Winter’s Bone predominately implements audience positioning in an attempt to incite empathy towards Ree and her struggles within an oppressive patriarchal society. Through the use of cinematography, mise-en-scène, sound, and dialogue, Granik encourages the spectator to support Ree’s actions. Conversely, No Country For Old Men subverts the spectator’s preconceptions of narrative conventions through the use of unorthodox narrative techniques alongside an inherently ambiguous thematic tapestry. The Coen brothers encourage active spectatorship to be exercised throughout, allowing for layered meanings of the film to be deciphered. Both films aptly demonstrate the power filmmakers possess towards shaping how a spectator responds to a film.

Essay – Version 1

Throughout both Winter’s Bone (Debra Granik, 2010) and No Country For Old Men (Joel and Ethan Coen, 2007), the respective filmmakers persistently attempt to control the spectator’s response in a variety of faceted means. Winter’s Bone implements audience positioning in ways that attempt to elicit empathy within the viewer towards the protagonist, Ree, and her struggles within an oppressive patriarchal society. Granik claims that the film is “a feminist film about an anti-feminist world”, implying that the preferred reading is one in which the viewer is encouraged to support Ree’s actions throughout the film. Conversely, the Coen brothers set out to actively subvert the spectator’s preconceptions of narrative in No Country For Old Men, by encoding the film with an ambiguous thematic substance, challenging the spectator’s morals and ideologies. A passive spectator would even perhaps argue that the film is ‘unsatisfying’, as it does not conform to the conventions of a traditional narrative.

During the opening sequence of Winter’s Bone, the viewer is immediately encouraged to emphasise with Ree‘s struggles in an impoverished and oppressive patriarchy. The film opens with a non-diegetic lullaby, immediately connoting a sense of intimate maternity. Cutting to a wide shot, the children are framed behind the bars of a bed-frame — implying to the viewer that they are trapped within their environment. This opening sequence also conveys the cyclical nature of nurturing – Ree’s sister, Ashlee takes care of her toy kitten, implying the idea that she herself has been nurtured by Ree. Mise-en-scène is also implemented within the domestic landscape, being littered with waste and abandoned items. This, alongside the characters clothing being ragged and humble, emphasises the poverty-stricken way of life Ree and her family leads, positioning the audience as to empathise with them.

Ree’s bravery and defiance within an oppressive patriarchy is also displayed to the spectator during the ‘cattle market’ sequence, during which Ree calls for Thump Milton at the top of her lungs. Milton is unable to comprehend her, further reinforcing the invisible yet prevalent divide between the male and female worlds. Alongside this, the non-diegetic composed score becomes discordant, creating a sense of urgency. It is layered in tandem with the cries of the cattle, creating a sensory overload which reflects Ree’s distraught state of mind. This is another example of audience positioning used in an attempt to control the spectator’s response – eliciting empathy towards Ree in this case.

An example of taking a negotiated reading by using active spectatorship occurs during the ‘squirrel dream’ sequence. During this sequence, Granik utilises unorthodox techniques such as black and white grainy footage filmed with a cheap handheld camera. Granik also implements a 4:3 aspect ratio, further contributing to the surreal nature of the sequence. A negotiated reading would argue that the squirrel in the sequence is perhaps a metaphor for Ree – as both are victims of a disrupted naturalistic environment. The danger faced by the squirrel is displayed through its shuddering fear, captured through the camera’s rapid and disorienting movements. A jarring diegetic chainsaw sound promptly enters the mix, perhaps being representative of the oppressive patriarchy that endangers Ree’s peaceful existence. A worms-eye-view shot of the trees is also used, displaying the squirrel, and by extension, Ree, as dwarfed, emphasizing her vulnerability within an oppressive patriarchal society. This reading is not explicitly conveyed by the film, but is instead only able to be inferred through active spectatorship. Each viewer will interpret this sequence in a slightly different way, exemplifying how this sequence is an example of Debra Granik attempting to control the spectator’s response.

Throughout the film, Ree’s uncle Teardrop is characterised in ways that illustrate him as a symbol of toxic masculinity – a notion that is able to be unravelled through active spectatorship. In the ‘squirrel gutting’ sequence, a focus pull is implemented to draw the spectator’s attention towards Teardrop as he approaches Ree. During their conversation, Teardrop offers some drugs to Ree, asking if she “has the taste for it yet”. Ree adamantly refuses, being indicative of her mental fortitude and purity that she possess over Teardrop, positioning the audience in a way that encourages the spectator to condemn Teardrop. In addition, during the closing sequence, Teardrop vows to seek revenge on the man that killed Ree’s father, reinforcing the cyclical nature of violence and highlighting the idea that Teardrop’s misguided sense of loyalty is a negative force, and that it is ultimately through the actions of women that the problems in the film are resolved. This further encourages the viewer to support Ree’s actions, framing Teardrop as a force of evil.

In contrast to Winter’s Bone’s attempts to control the spectator through the use of audience positioning which encourages the viewer to empathise with Ree, No Country For Old Men controls the viewer’s response by instead setting out to actively subvert the spectator’s preconceptions of narrative conventions, weaving an ambiguous thematic substance that pervades the film. Through this, active spectatorship is required to decipher a particular meaning from the Coen brothers’ enigmatic masterpiece.

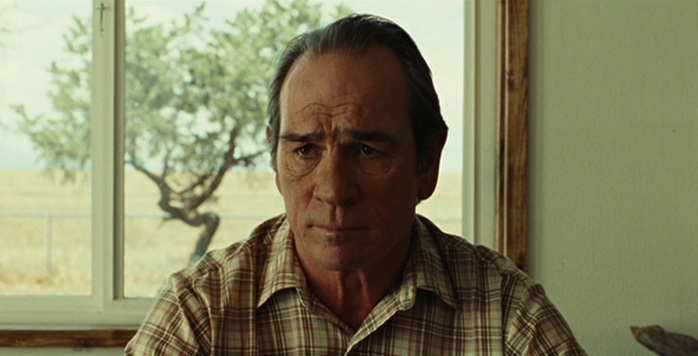

The opening scene of the film immediately subverts the spectator’s expectations by beginning with a non-diegetic monologue delivered by Sheriff Ed Tom Bell. The monologue does not serve to provide exposition, but is instead an introspective monologue in which the sheriff reminisces upon the senselessly violent crimes that he has dealt with throughout his career. The viewer is left to question the meaning of this monologue, encouraged to become an active spectator by unravelling the themes of nihilism and determinism that the monologue touches upon. The preferred reading of the film is arguably for the viewer to side with the sheriff, sympathising with his disillusionment towards the nihilism that permeates Texas. This opening scene exemplifies the rejection of the hypodermic needle model which suggested that audiences were to blindly accept any messages presented within media.

Instead of being rewarded with a traditional showdown between the three main characters, the spectator’s expectations are instead subverted by the final scene of the film, with it being a pensive recount of the sheriff’s dreams. The Coens’ decision to end the film with an abrupt cut to black controls the viewer’s response in an interesting way – the spectator is forced to dwell upon the meanings of the sheriff’s dream as the credits roll. While a passive spectator would argue that this final scene is an unsatisfying conclusion to the film, an active spectator would perhaps argue that Ed Tom’s dream is symbolic of the sheriff following his father towards his impending demise.

No Country For Old Men also subverts the preconception of unconditionally supporting the protagonist’s actions during the first scene involving the character of Llewelyn Moss. During the scene, the viewer bears witness to Llewelyn’s selfish actions. He chooses to not give water to a dying man, instead taking the briefcase containing $2 million. Viewers are encouraged to employ active spectatorship – Llewelyn’s actions are arguably morally reprehensible and selfish, but this idea is not explicitly conveyed to the audience. Individual spectators are instead encouraged to decide whether or not Llewelyn’s actions are morally just.

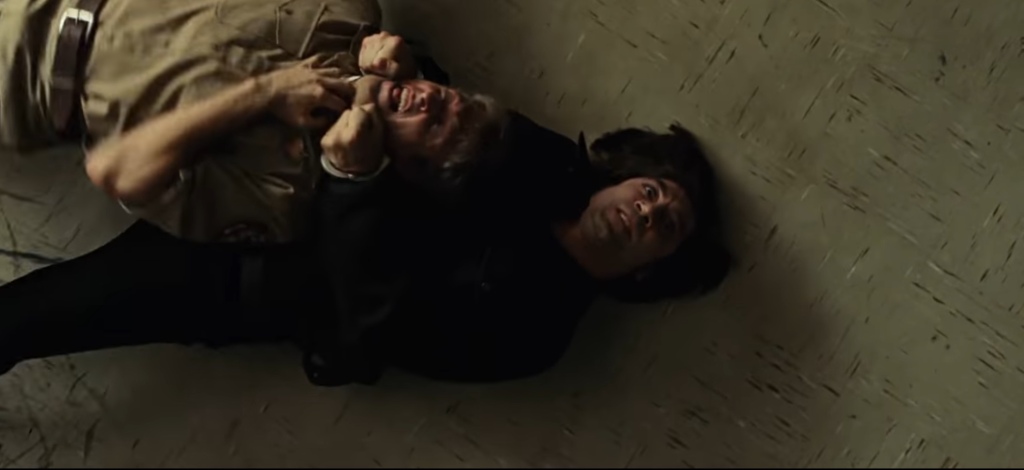

The nature of Llewelyn’s death, being abrupt and offscreen, also serves as a means of controlling the spectator by subverting the their expectations. After a seemingly mundane and innocuous conversation between Llewelyn and a woman sitting in a pool takes place, the scene abruptly fades to black, before we cut to Sheriff Ed Tom Bell’s point of view. The Coens’ employ a POV shot of the sheriff running towards the crime during which camera shake is employed to heighten the tension. Ed Tom, however, is too late – the inevitable causality of death has already taken effect. The fact that Llewelyn is killed in such an unheroic manner by a group of characters we have never been introduced reinforces the futility of humanity, providing acute shock value for the viewer in which their response is controlled by the filmmakers.

Throughout the film, ruthless hitman Anton Chigurh commits a series of senseless, brutal murders in pursuit of the money-filled briefcase. However, Anton’s motivations that fuel his actions are highly ambiguous, choosing his victims seemingly at random, rather than just those who obstruct his aims. The meanings behind Anton’s actions are to be extracted by the viewer – by employing active spectatorship, the Coens encourage the viewer to uncover the truth behind Anton’s murders. During the ‘call it, friend-o’ sequence, Anton leaves a perfectly innocent man’s fate up to a 50/50 coin flip, perhaps reinforcing his nihilistic belief that human life is meaningless and arbitrary. After the owner argues that he didn’t put anything up to win on the coin flip, Anton informs the man that “you’ve been putting it up your whole life, you just didn’t know it”, suggesting that the end of the man’s meaningless existence has already been decided. Alongside this, during the closing sequence, it is implied that Anton does indeed kill Carla Jean. Using active spectatorship, the viewer is able insinuate that Carla is dead after Anton checks his shoes for blood – an action that he has performed many times over the course of the film. An implied reading of the scene argues that due to the fact that Carla did not let the coin decide her fate, Anton decides to end her life purely due to his belief in the insignificance of human life.

In conclusion, Winter’s Bone and No Country For Old Men use starkly contrasting methods in order to control the viewer’s response. Winter’s Bone predominately implements audience positioning in an attempt to incite empathy towards Ree and her struggles within an oppressive patriarchal society. Through the use of cinematography, mise-en-scène, sound, and dialogue, Granik encourages the spectator to support Ree’s actions to support her impoverished family. Conversely, No Country For Old Men subverts the spectator’s preconceptions of narrative conventions through the use of unorthodox narrative techniques alongside an inherently ambiguous thematic tapestry. The Coen brothers encourage active spectatorship to be exercised throughout, allowing for layered meanings of the film to be deciphered. Both films aptly demonstrate the power filmmakers possess towards shaping how a spectator responds to a film.

You must be logged in to post a comment.