The concept of narrative involves the discussion of a variety of collective ideas that link to how the story of a film is presented to the viewer, alongiside how the story is internalised. This blog will explain the key narrative functions, as well as how Pulp Fiction (Quentin Tarantino, 1994), in many cases, does not conform to these narrative conventions.

Story, plot, and narrative

The overall concept of narrative can be subdivided into three ideas: story, plot, and narrative.

Story is defined as “everything that happens in the fictional world between the beginning and the end, including events that viewers infer or presume to have happened”. In essence, this means that story is the collection of narrative events that both occur and are implied throughout the film.

Plot is defined as “what viewers see on screen and hear on the soundtrack to allow them to construct a story in their heads. Plots can begin anywhere on the chain of story events and can leap backwards and forwards in time and space.” Plot expands upon the initial concept of ‘story’ by introducing the idea of the viewer’s internal contextualisation of narrative events. Plot also hints at the idea of nonlinearity, which suggests that not all stories must be told in a rigidly chronological order.

Narrative is defined as “the flow of story information constructed by the plot at any given moment. Narrative implies a point of view, which may be that of one of the characters or of an omniscient, all-seeing narrator.” Narrative introduces the idea of using different character perspectives in order to enrich the meaning of a film. Switching perspectives often gives the viewer new insight into the characters’ motivations, as well as the meaning behind the events occurring onscreen.

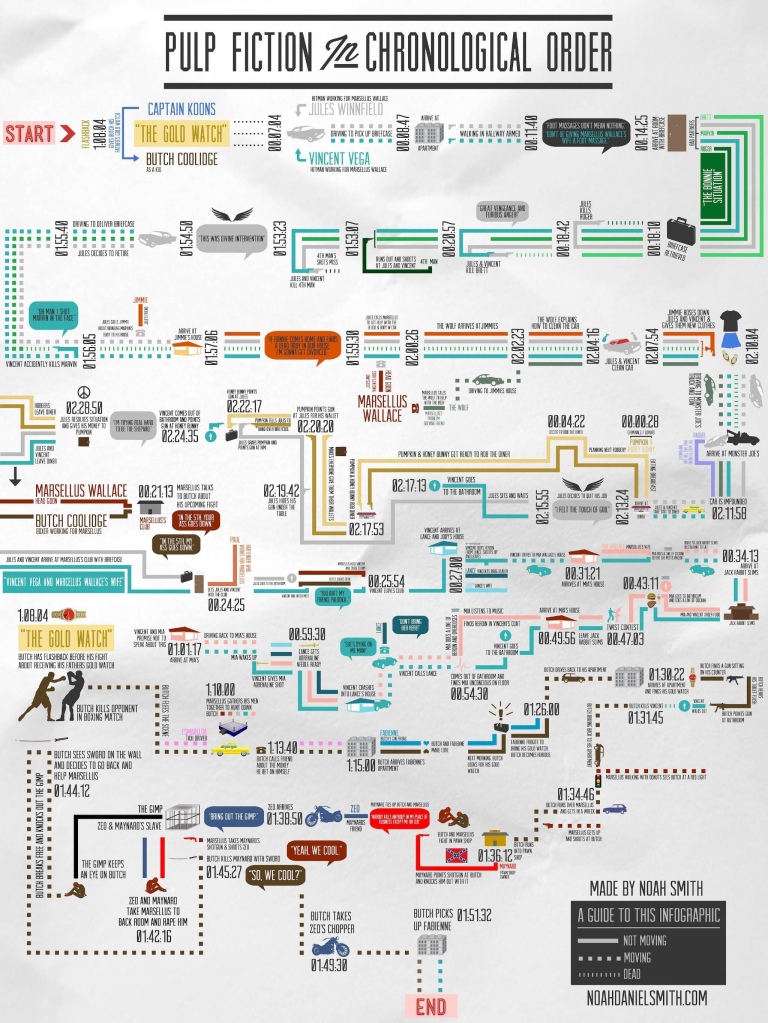

In the case of Pulp Fiction, Tarantino utilises each of these narrative elements in order to create a unique and satisfying experience. The story of the film is relatively simple, with the film containing four episodic chapters with intertwining characters and events. On the other hand, the plot of the film is constructed in a highly nonlinear and convoluted manner. Although each chapter itself has a linear structure, the order in which it is shown to the viewer is non-chronological. This fragmentation of the plot creates an underlying sense of anticipation. Due to the fact that the viewer is witnessing events out of order, we expect to see the repercussions of these events later in the film.

Pulp Fiction also uses the aforementioned multi-character perspective idea, affecting the narrative of the film. For example, the restaurant robbery scene is displayed to us initially from the perspectives of Pumpkin and Honey Bunny, thus diverting our attention towards the pair as characters. We are engaged by their conversation suggesting a potential robbery and are subsequently teased by the very start of it. Tarantino provides closure on this event at the very end of the film, during which Jules and Vincent are the central focus. We now root for them, as the narrative focus has been shifted, affecting the viewer’s perception of events. On the surface, Pulp Fiction’s multiple storylines could be considered ‘clichéd’ or archetypal, due to each event that occurs being nothing that is wholly original. The predominant pleasure that the film provides is ultimately the meticulously crafted narrative structure.

The Three Act Structure

Another touchstone of storytelling is the three act structure – a model widely utilised throughout fiction. Dividing a narrative into three clear-cut sections, the typical structure involves three acts (setup, confrontation, resolution). In the case of Pulp Fiction, each chapter of the film loosely follows this structure. For example, during Butch’s story: Act 1 displays Butch being paid by Marsellus to throw his next fight, Act 2 is the sequence in which Butch returns to his apartment through to the pawn shop scene, finally concluding with Act 3 in which Butch saves Marsellus and returns to Fabienne.

By only displaying fragmented acts of the multiple storylines in quick succession, Tarantino subverts the viewer’s preconceived expectations of what a typical narrative structure entails.

Types of Narrative

There are three main types of narrative, being: linear, circular, and episodic.

Linear narrative “starts at the beginning, and continues in the order that events happen up to the end.” This is the most conventional and simple narrative structure, displaying events in a straight forward and chronological order.

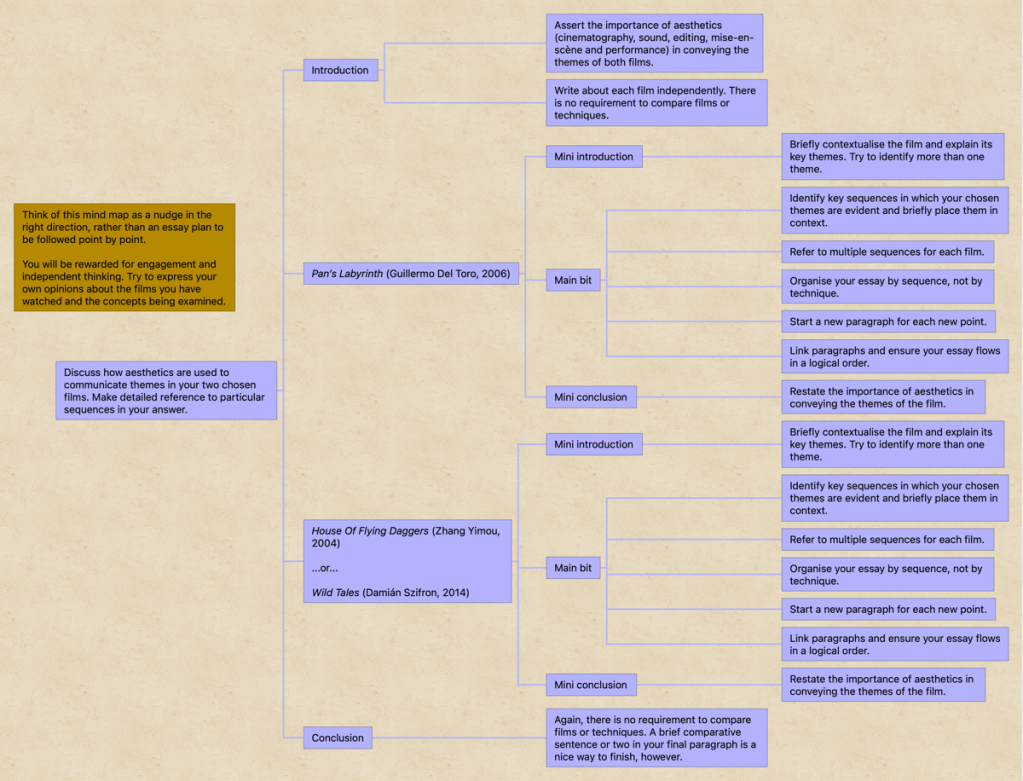

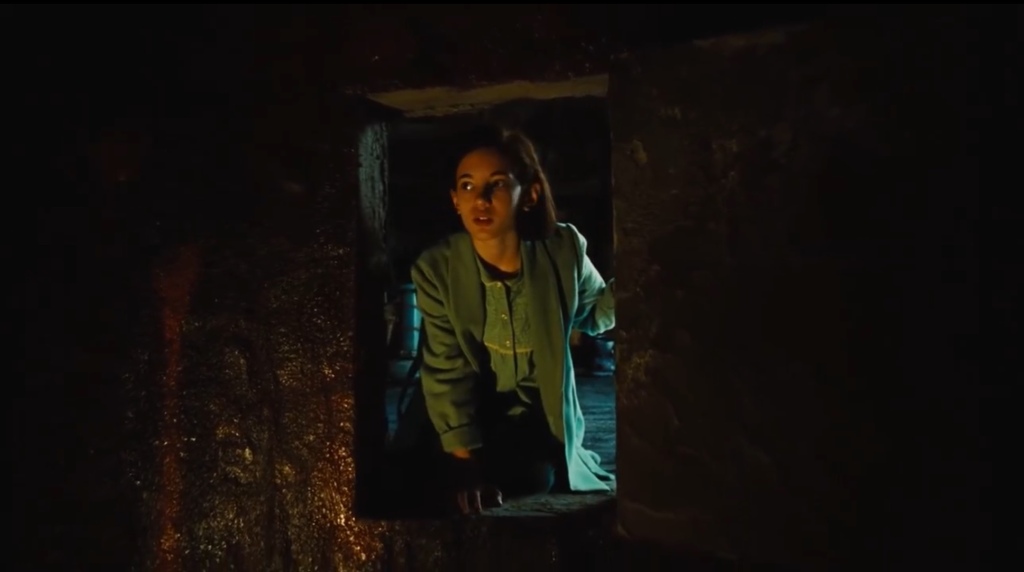

Circular narrative “starts at the end, then goes back in time to return to this point later on.” This is an interesting story structure, creating an immediate narrative hook to reel in the viewer’s attention. Over the course of the film, this memory of this event will linger in the viewer’s mind and a sense of satisfaction will be provided when the event is finally reprised. A example of this can be seen in Pan’s Labyrinth (Guillermo del Toro, 2006). Ofelia’s death is initially displayed to the viewer in reverse at the very start of the film, and is later returned to at the end, by which point we understand the context surrounding the previously shocking and unexpected event.

Episodic narrative “has clearly separated sections, often broken up by a title, date, or a cutback to a narrator.” This allows a film to tell more than one story, perhaps in a portmanteau style. An example of this can be seen in Wild Tales (Damián Szifron, 2014) in which five stories are told, each connected by the theme of revenge.

In the case of Pulp Fiction, Tarantino utilises elements of all three modes of narrative throughout the film. For example, large chunks of the film are displayed in a wholly linear fashion, such as Vincent and Mia’s date, during which Tarantino employs techniques such as continuity editing. The narrative of the film could also be considered circular, due to the fact that the the robbery scene in the diner acts as both a prologue and epilogue section. Pulp Fiction could also be considered episodic too, seeing as the film is broken down into chapters that are signalled by intertitles.

Prolepsis (flash-forward) and Analepsis (flashback)

A pair of techniques that are often utilised within storytelling are prolepsis and analepsis.

Prolepsis (often referred to as a flash-forward) is a “temporal edit to a later point in time”. This dramatic device can be used to foreshadow and tease future events to the viewer.

Conversely, analepsis (often referred to as a flashback) is a “temporal edit to an earlier point in time”. Analepsis can be utilised to perhaps provide contextual information, displaying past events that will become relevant to the current narrative at a later point.

Tarantino uses both prolepsis and analepsis at specific points throughout Pulp Fiction. Namely, a flash-forward sequence occurs during The Bonnie Situation. This hypothetical sequence displays Bonnie returning home from work to find the gangsters handling a body in the living room. A flashback is used as a preface to Butch’s story – Captain Koons monologues to a young Butch, explaining the importance of the titular gold watch. This later contextualises Butch’s return to the apartment in order to reclaim this watch.

Ellipsis

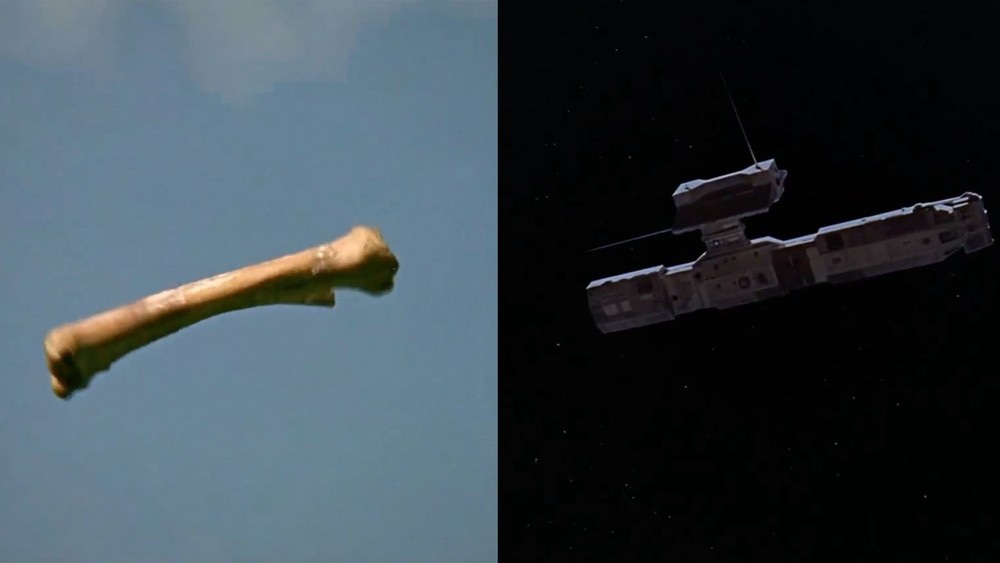

This narrative device is defined as “the emission of a section of the story that is either obvious enough for the audience to fill in, or concealed for a narrative purpose, such as suspense or mystery”. Ellipsis is widely used throughout film, leaving the viewer to frequently assume that events have occurred. For example, unless it possesses significant importance, a character’s physical journey from point A to point B is not usually displayed to the viewer due to the fact that we can safely assume how they reached this destination. Ellipsis is also used for much more dramatic purposes, such as in 2001: A Space Odyssey (Stanley Kubrick, 1968) in which Kubrick famously match cuts from a spinning bone to a spaceship, effectively fast-forwarding the entire evolution of humankind.

Pulp Fiction uses ellipses to withhold important information from the viewer at specific points in the film, ultimately providing a sense of gratification when the viewer pieces the events together. A clear example of this is during the shared prologue and epilogue of the film – the diner scene. During the prologue, we are only aware of Pumpkin and Honey Bunny’s presence and only later learn during the epilogue that Jules and Vincent are in fact sitting in the same location.

Narrative Viewpoint

Narrative viewpoint is the lens through which we view the plot. There are three main types of narrative, being: restricted, unrestricted/omniscient, and voiceover/narrative.

A restricted narrative viewpoint is when “the audience only know as much as the main character.” This viewpoint is often used to create a sense of mystery; due to the viewer only having the knowledge of the protagonist they are also encouraged to connect with them on a deeper level.

An unrestricted/omniscient viewpoint is when “the audience sees aspects of the narrative that the main character does not.” This type of viewpoint often creates dramatic irony – a useful narrative device that creates tension and suspense.

Voiceover/narration is “an omniscient or subjective non diegetic verbal commentary.” Narration is often used in films such as Fight Club (David Fincher, 1999) and GoodFellas (Martin Scorsese, 1990) to provide a direct line of communication between the characters and the viewer. However, voiceover often provides a biased perspective on events. Despite this, the two aforementioned films utilise this to their advantage.

Tarantino combines both restricted and unrestricted viewpoints throughout Pulp Fiction, providing a sense of satisfaction for the viewer in both cases. An example of a restricted viewpoint in the film is during the scene where Jules and Vincent collect the briefcase from the apartment. During this scene, the viewer is unaware that there is a man in the bathroom with a gun and we only learn this fact once we return to the scene later in the film.

An unrestricted viewpoint used in the film is the scene where Mia overdoses on heroin. Earlier in the film, Vincent is displayed buying powered heroin from Lance. At Mia’s apartment, Vincent leaves this heroin on the table, prompting Mia to snort a line after getting back from Jack Rabbit Slim’s, as she assumes that it is cocaine. With the use of an omnipotent narrative viewpoint, Tarantino creates dramatic irony during this scene, establishing suspense and drama.

Narrative Devices

These are an assortment of techniques used frequently throughout storytelling for a variety of intended effects. These include title cards, intertitles, chaptering, and audience positioning.

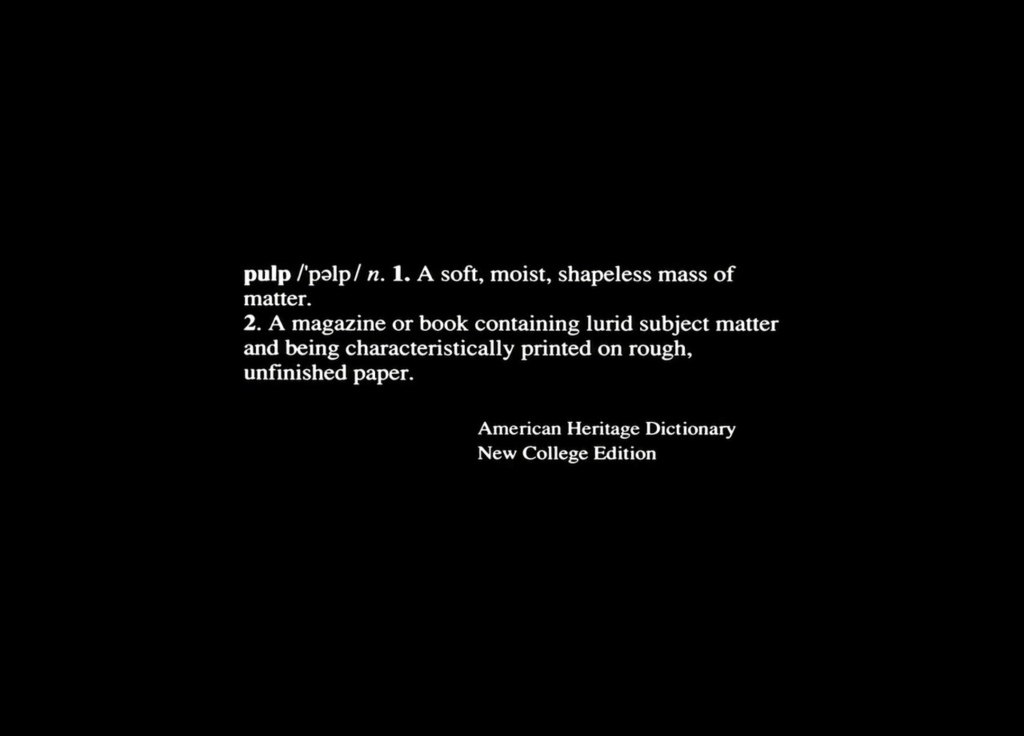

Title cards are “printed contextual text at the start of the film”. Pulp Fiction opens with a dictionary definition of “pulp”, displaying the two meanings to the viewer. The first meaning is “a soft, moist, shapeless mass of matter” which perhaps hints at the overall narrative structure of the film. The second definition, “a magazine or book containing lurid subject matter and being characteristically printed on rough, unfinished paper” is suggestive of the “Pulp Fiction” present throughout. The events and characters are both highly archetypal and cliched, and this idea is immediately suggested by the dictionary title card.

The second narrative devices is intertiles, which are instances of “printed text or narration shown between scenes”. Popularised by silent filmmakers such as Buster Keaton, this technique was to convey expositional information that could not be told through silent action. As such, intertiles are not present throughout Pulp Fiction.

Chaptering is the “division of a narrative into distinct, labelled units.” Linking to the aforementioned episodic narrative structure, this narrative device allows filmmakers to present multiple, clear-cut storylines. Tarantino employs chaptering to divide the three interconnected storylines into distinct episodes of the film. These chapters include “Vincent Vega and Marcellus Wallace’s Wife”, “The Gold Watch”, and “The Bonnie Situation”.

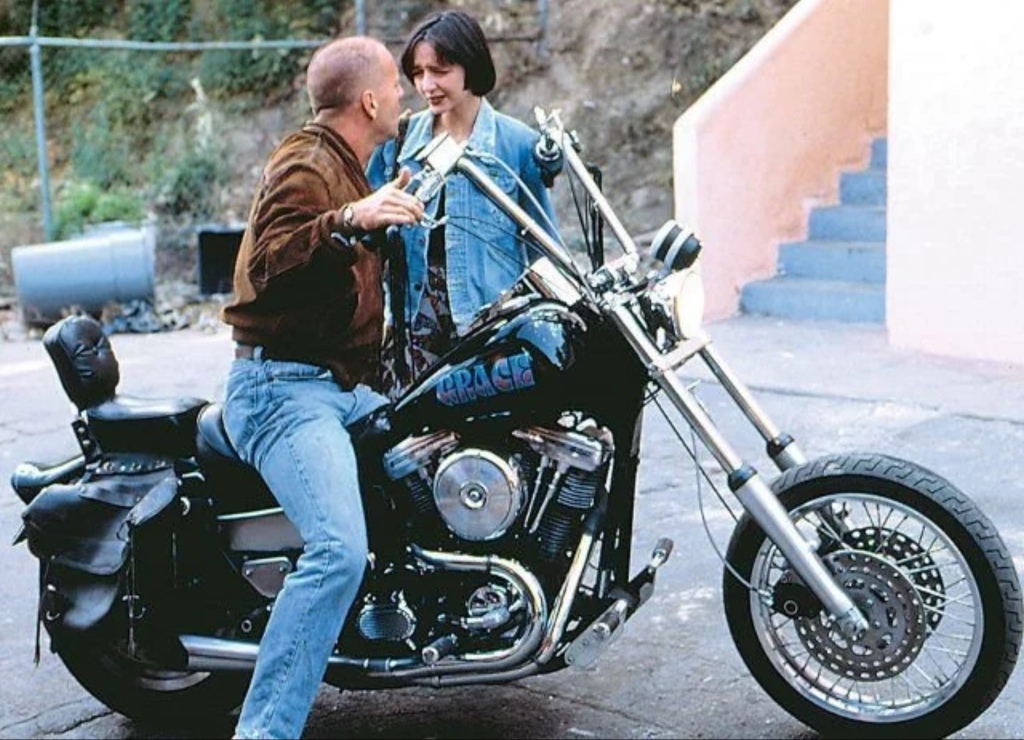

Audience positioning is a nuanced and engaging narrative device that involves “how the narrative encourages or discourages audience sympathies and reactions.” In Pulp Fiction, this causes the viewer to empathise with different characters in different ways at different times. The characters, who we initially view as mere archetypes of the crime genre, are thus humanised by how Tarantino positions the audience. We enjoy being in the company of Vincent and Jules, two highly repugnant gangsters who kill people for money are presented as a charismatic and comedic duo. The viewer is encouraged to sympathise with an array of despicable characters who we initially wouldn’t.

Conversely, characters such as Zed and Maynard are positioned as antagonistic forces during Butch’s story, despite perhaps being no worse than the protagonists that we root for. The audience is also positioned to view different characters as the ‘protagonist’ during certain section of the film. For example, we subconsciously root for Pumpkin and Honey Bunny during the prologue, but support Jules and Vincent during the epilogue as the couple are framed as the antagonists within the reprise of the scene. The focus often shifts fluidly without the viewer noticing, an example being when the shift focuses from Vincent onto Mia when they return to the apartment.

Narrative Theories and Theorists

A number of narrative theorists formulated specific theories concerning storytelling, characters and structure. These include Vladimir Propp, Tzvetan Todorov, Roland Barthes, and Claude Levi-Strauss. Taking these theories into account, it becomes clear that Pulp Fiction does not conform to typical narrative conventions.

Vladimir Propp was a Soviet literary theorist who studied Russian folklore and created two narrative theories. He first theorised the concept of the seven character archetypes that all characters in fiction must conform to. These include the Hero, Villain, Princess, Donor, Dispatcher, Helper, and the False Hero. Each of these character types supposedly serve a specific purpose in each narrative. In Pulp Fiction’s case, Tarantino does not conform to the idea of the seven character types due to the fact that we do not follow a single journey, and each character in the film fulfils multiple roles at particular times.

Propp’s second theory involved the idea of 31 narrative functions that every story would contain at least some of, in a particular pre-conceived order. Again, this theory does not apply to Pulp Fiction seeing as the theory only applies to stories told in a chronological order.

Tzvetan Todorov was a Bulgarian-French historian who created the ‘Equilibrium Theory’, stating that every story is made up five stages. These include equilibrium, disruption of equilibrium, recognition of disruption, resolution, and new equilibrium. Once again, this theory does not apply to Pulp Fiction – its fragmented narrative subverts both this theory alongside the viewer’s prior knowledge of narrative structure.

Roland Barthes was a French essayist who created the ‘Narrative Codes Theory’, stating that all stories are made up of two types of codes. Firstly, the ‘action code’ involves a physical event that is displayed, prompting the viewer to ponder the consequences of it. An example of an action code in Pulp Fiction is the scene where Vincent accidentally shoots Marvin in the face. The viewer is left in awe of this shocking event, causing them to possess an intrigue as to what the consequences might be.

The second type of code created by Barthes is the ‘enigma code’. This idea depicts an intriguing event that creates a sense of mystery, and prompts the viewer to acquire an interest in unravelling the mystery. Tarantino employs this idea in Pulp Fiction by using the elusive briefcase to create a sense of intrigue. Furthermore, the viewer never actually finds out what is in the briefcase, letting the mystery remain unsolved forever.

Claude Lévi-Strauss was a French anthropologist who created the theory of ‘Binary Opposition’. He argued that audience engagement is driven by tension between binary opposites, such as: good vs evil, race, and social rankings. Whilst binary opposites are not a prominent theme featured throughout Pulp Fiction, certain predicaments do arise from opposing views – an example being when Mia wishes to dance, but Vincent does not. Instead, Tarantino paints characters who possess morally grey compasses and exist between the binary idea of good vs evil.

In conclusion, Tarantino subverts both the audience’s and theorists’ preconceived notions of what a conventional narrative is made up of. Instead, he chooses to present the film in a refreshing and unique manner, utilising an array of narrative devices at his disposal whilst maintaining a sense of underlying individuality.

You must be logged in to post a comment.