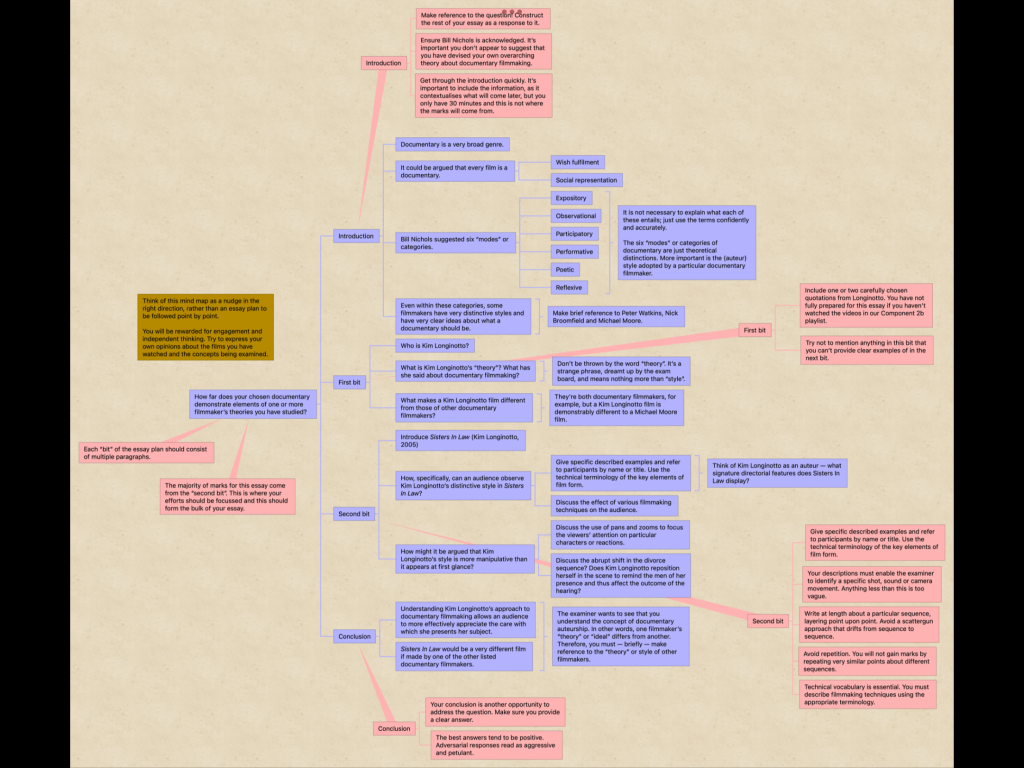

How far does your chosen documentary demonstrate elements of one or more filmmaker’s theories you have studied?

Autumn 2020

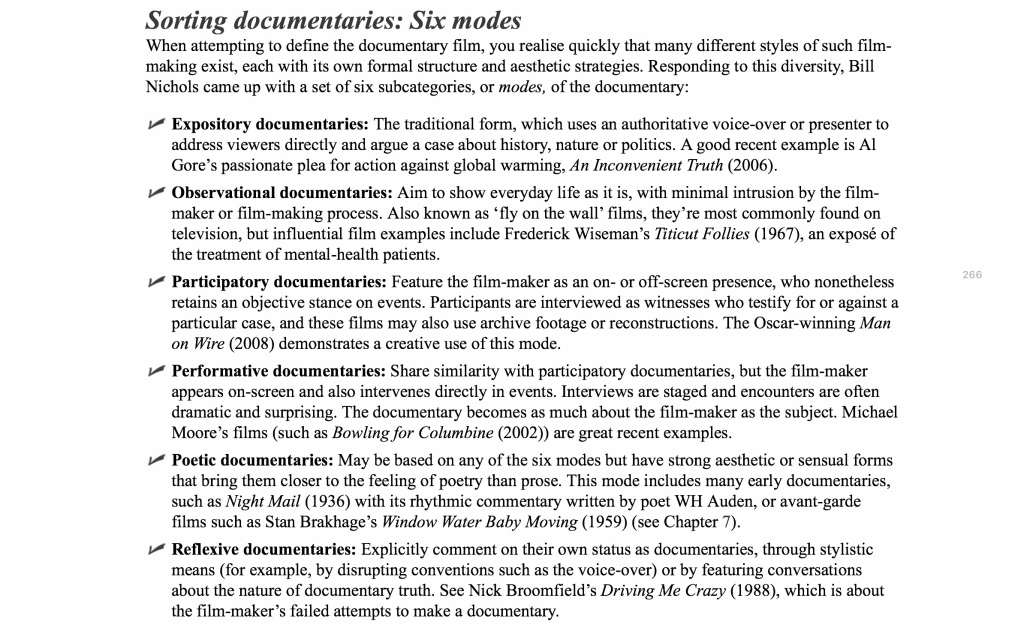

Introduction: Defined as a film that uses pictures or interviews with people involved in real events to provide a factual report on a particular subject, it can be difficult to pinpoint what a documentary exactly is. Bill Nichols, a documentary theorist, has argued that all films fall into one of two categories of documentary – being wish fulfilment and social representation. The latter of which can be further categorised into one of Nichols’ six ‘modes’ of documentary, including: expository, observational, participatory, performative, poetic and reflexive.

Even still, the vast majority of documentaries blur the line between modes and can be easily argued to be categorised under more than one. A clear example of this is The War Game (Peter Watkins, 1965) which can be classified in particular as an observational or participatory documentary. These filmmakers such as the aforementioned Peter Watkins, as well as those such as Michael Moore and Nick Brookfield, are attempting to create a wholly unique and intriguing documentary. Therefore, their aims involve preventing their films from being categorised under a flawed, preconceived system created by a single person.

Section 1: Introduce Kim Longinotto and her style. Reference her ideologies and theories.

Observational, Cinema verite, “would like to watch herself”, “feels very uncomfortable asking people to do things”, panning over cuts, Aaton Super-16 camera over digital technology (acts as the cinematographer and camera operator).

Section 2: Introduce Sisters in Law.

Handheld, long-takes, opening score is the only non-diegetic sound, temporal editing, tilts, subtitles, editing compresses events, zooming (Vera and Manka), priorities authenticity over aesthetics, two shots separates the law, reactionary shots, domestic life separations, over-the-shoulder (Amina), gender inequality (observational documentary is successful), playing up to the camera (aunt and council)

Conclusion

Essay – Version 1

Defined as a film that uses pictures or interviews with people involved in real events to provide a factual report on a particular subject, it can be difficult to pinpoint what a documentary exactly is. Bill Nichols, a documentary theorist, has argued that all films fall into one of two categories of documentary: wish fulfilment and social representation. The latter of which can be further categorised into one of Nichols’ six ‘modes’ of documentary, including: expository, observational, participatory, performative, poetic and reflexive.

Even still, the vast majority of documentaries blur the line between modes and can be easily argued to be categorised under more than one. A clear example of this is The War Game (Peter Watkins, 1965) which can be classified in particular as an observational or participatory documentary. These filmmakers such as the aforementioned Peter Watkins, as well as those such as Michael Moore and Nick Broomfield, are attempting to create a wholly unique and intriguing documentary. Therefore, their aims involve preventing their films from being categorised under a flawed, preconceived system created by a single person.

Despite this, a number of documentarians’ work can indeed be categorised under a single mode of documentary, one example being Kim Longinotto. Known for making observational documentaries that spread awareness of discriminatory oppression towards women, Longinotto has stated that “real life is often more surprising and extraordinary than we can imagine”. Incoporating the cinéma vérité style of filmmaking into her films, Longinotto attempts to create films that she “would like to watch” herself. Her films are characterised by an authentic, uninterrupted portrayal of events which supports her ideology of believing that films should not explicitly state what the viewer should think and feel over the course of the film. This juxtaposes the styles of documentarians such as Michael Moore, who establishes an extremely noticeable and cynical presence throughout each of his films.

Throughout her films, Longinotto prefers to pan the camera rather than use cuts when a new person begins to talk. This places the viewer within the “eyes” of the camera and establishes a much more authentic and apparent perspective. Although she can never be seen in her documentaries, Longinotto acts as the cinematographer and camera operator for each of her films. Because of this, she shoots each of her films with an Aaton Super-16 model stating that she “loves the steadiness” of it. Often employing only one other co-director, it is important for her to film with a camera that she is extremely familiar and comfortable with.

One film that best demonstrates the filmmaking theories of Kim Longinotto is Sisters in Law (2005). Throughout the film, Longinotto employs the key elements of film form in a wide variety of ways in order to produce an unobtrusive and authentic observational documentary.

Firstly, Longinotto employs the use of her aforementioned Aaton Super-16 handheld camera throughout the duration of the film. This can initially be seen in the opening shot of the film – a wide shot out of a car window that exhibits the rural, poverty-stricken landscape of Kumba, Cameroon. The use of a handheld camera without a tripod is perhaps used due to the fact that it is less conspicuous than a tripod. In theory, the subjects’ actions portrayed throughout the documentary will be more genuine because of this, demonstrating Longinotto’s theory of authenticity. Throughout this long take, a non-diegetic score is present in the mix – a plucked acoustic guitar that evokes a sense of pastoral imagery. After the score gradually lowers in the mix, the diegetic ambience of Kumba enters.

From this point forward, every sound in the mix is both diegetic and recorded on set. Alongside this, the lighting is all naturally captured and is merely a reflection of reality. All of the mise-en-scène found within each scene is naturally occurring in order to display an entirely authentic depiction of the scenarios. Alongside this, no contextual information is explicitly stated to the viewer – supporting Longinotto’s aforementioned statement about implicit information. After an apt use of temporal editing to demonstrate the journey into the village, Longinotto employs her first of many uses of camera panning. Acting as the proxy for the viewer, the pan exhibits the view of the rural setting. Alongside this, panning is used to focus on each subject as they begin to talk, replicating the notion of eyes following a conversation.

Within the village, Longinotto utilises a number of spontaneous camera movements – tracking subjects by tilting the camera up and down. Scenes are mostly captured with a two camera setup, operated by Longinotto herself, as well as co-director Florence Ayisi. Thus, each scenario can be captured by two opposing angles and cut together by Longinotto in post-production. During a court meeting between Vera Ngassa (the state prosecutor) and a couple, Longinotto employs the zoom feature in real time to focus in on a closeup of Vera. Due to autofocus taking effect, the footage briefly goes out of focus before refocusing on the closeup. This demonstrates to us Longinotto’s ideological priority of accuracy and authenticity over aesthetic perfection.

Each legal case is interspersed with brief, ambient scenes which display domestic life within the village. Throughout these, Longinotto will typically film in a single location and capture each and every event that occurs, even seemingly trivial scenarios. In effect, this implicitly contextualises the setting and cultural characteristics of the Cameroonian village of Kumba. This demonstrates her theory of capturing “real life” throughout her unassuming style of filmmaking.

Zooms are often used throughout the film, another example being during the Manka Sequence in which Longinotto zooms in on a young girl’s wounds. Through this, a high-angle closeup is created which exhibits the scars and wounds she possesses. This subtle example of camera manipulation instills empathy within the viewer and reinforces Manka’s vulnerability. Longinotto also separates the two sides of the law by cutting between a three-shot of Stephen, Manka and the aunt, and a mid-closeup of Vera which is captured by the second camera. This apt use of editing is noticeable to the viewer, but unobtrusive to the portrayal of events. During the confrontation, the camera also occasionally focuses on the reaction of the subject being spoken to, rather than the person speaking. Through this reactionary shot equivalent, the viewer is able to soak in each of the subject’s live reactions to the events that occur. During the aunt’s panic-stricken rebuttal, Longinotto utilises a closeup on her face. Through this, it becomes clear to the viewer that the aunt is playing up to the camera. Her exaggerated crocodile tears and frantic justifications purports a sense of vulnerability, but the viewer is likely able to see through this due to Longinotto’s intelligent camerawork.

This instance of the camera having a direct impact on events can also be seen within the Divorce Sequence. After the divorce is granted to Amina by the council who almost exiled her from the country, the man now noticeably plays up to the camera, stating that “that’s what Cameroon wants! We don’t want problems”. Vera’s prior empowerment over the abusive aunt juxtaposed with the oppression faced by Amina within this sequence epitomises the different roles in society held by women that Longinotto endeavours to bring to light.

In conclusion, Kim Longinotto’s filmmaking theories, employed throughout Sisters in Law, can be characterised at its core, by her proactive avoidance of intervention which is typically found throughout other documentaries. For example, if Nick Broomfield or Louis Theroux had made this film, their respective strong characters would be felt across the duration of the film. In the case of Longinotto, Sisters in Law’s approach allows for a much more subtle and thoughtful viewing experience, in which the viewer is able to draw their own conclusions through Longinotto’s implicit manner of filmmaking.

Essay – Version 2

Defined as a film that uses pictures or interviews with people involved in real events to provide a factual report on a particular subject, it can be difficult to pinpoint what a documentary exactly is. Documentary theorist Bill Nichols’ six ‘modes’ of documentary can be used to categorise each and every documentary under a particular division.

Even still, the vast majority of documentaries blur the line between modes. A clear example of this is The War Game (Peter Watkins, 1965) which could be classified under more than one mode. This is because Watkins and other documentarians such as Michael Moore and Nick Broomfield are attempting to create a wholly unique and intriguing documentary. Their aims involve preventing their films from being categorised under a flawed and narrow-minded system.

Despite this, a number of documentarians’ work can indeed be categorised under a single mode of documentary, one example being Kim Longinotto. Known for making observational documentaries that spread awareness of discriminatory oppression towards women, Longinotto has stated that “real life is often more surprising and extraordinary than we can imagine”. Incoporating the cinéma vérité style of filmmaking into her films, Longinotto attempts to create films that she “would like to watch” herself. Her films are characterised by an uninterrupted portrayal of events which supports her ideology of believing that films should not explicitly state what the viewer should think and feel.

Throughout her films, Longinotto prefers to pan the camera rather than use cuts when a new person begins to talk. This places the viewer within the “eyes” of the camera and establishes a much more authentic and apparent perspective. Although she can never be seen in her documentaries, Longinotto acts as the cinematographer and camera operator for each of her films – often employing another co-director.

One film that best demonstrates the filmmaking theories of Kim Longinotto is Sisters in Law (2005). Throughout the film, Longinotto employs the key elements of film form in a wide variety of ways in order to produce an unobtrusive and authentic observational documentary.

Firstly, Longinotto employs the use of a handheld camera throughout the duration of the film. This can initially be seen in the opening shot of the film – a wide shot out of a car window that exhibits the rural, poverty-stricken landscape of Kumba, Cameroon. The use of a handheld camera without a tripod is perhaps used due to the fact that it is less conspicuous than a tripod. In theory, the subjects’ actions portrayed throughout the documentary will be more genuine because of this, demonstrating Longinotto’s theory of authenticity. Throughout this long take, a non-diegetic score is present in the mix – a plucked acoustic guitar that evokes a sense of pastoral imagery. After the score gradually lowers in the mix, the diegetic ambience of Kumba enters.

From this point forward, every sound in the mix is both diegetic and recorded on set. Alongside this, the lighting is all naturally captured and is merely a reflection of reality. All of the mise-en-scène found within each scene is naturally occurring in order to display an entirely authentic depiction of the scenarios. Alongside this, no contextual information is explicitly stated to the viewer – supporting Longinotto’s aforementioned statement about implicit information. After an apt use of temporal editing to demonstrate the journey into the village, Longinotto employs her first of many uses of camera panning. Acting as the proxy for the viewer, the pan exhibits the view of the rural setting. Alongside this, panning is used to focus on each subject as they begin to talk, replicating the notion of eyes following a conversation.

Within the village, Longinotto utilises a number of spontaneous camera movements – tracking subjects by tilting the camera up and down. Scenes are mostly captured with a two camera setup, operated by Longinotto herself, as well as co-director Florence Ayisi. Thus, each scenario can be captured by two opposing angles and cut together by Longinotto in post-production. During a court meeting between Vera Ngassa (the state prosecutor) and a couple, Longinotto employs the zoom feature in real time to focus in on a closeup of Vera. Due to autofocus taking effect, the footage briefly goes out of focus before refocusing on the closeup. This demonstrates to us Longinotto’s ideological priority of accuracy and authenticity over aesthetic perfection.

Each legal case is interspersed with brief, ambient scenes which display domestic life within the village. Throughout these, Longinotto will typically film in a single location and capture each and every event that occurs, even seemingly trivial scenarios. In effect, this implicitly contextualises the setting and cultural characteristics of the Cameroonian village of Kumba. This demonstrates her theory of capturing “real life” throughout her unassuming style of filmmaking.

Zooms are often used throughout the film, another example being during the Manka Sequence in which Longinotto zooms in on a young girl’s wounds. Through this, a high-angle closeup is created which exhibits the scars and wounds she possesses. This subtle example of camera manipulation instills empathy within the viewer and reinforces Manka’s vulnerability. Longinotto also separates the two sides of the law by cutting between a three-shot of Stephen, Manka and the aunt, and a mid-closeup of Vera which is captured by the second camera. This apt use of editing is noticeable to the viewer, but unobtrusive to the portrayal of events. During the confrontation, the camera also occasionally focuses on the reaction of the subject being spoken to, rather than the person speaking. Through this reactionary shot equivalent, the viewer is able to soak in each of the subject’s live reactions to the events that occur. During the aunt’s panic-stricken rebuttal, Longinotto utilises a closeup on her face. Through this, it becomes clear to the viewer that the aunt is playing up to the camera. Her exaggerated crocodile tears and frantic justifications purports a sense of vulnerability, but the viewer is likely able to see through this due to Longinotto’s intelligent camerawork.

This instance of the camera having a direct impact on events can also be seen within the Divorce Sequence. After the divorce is granted to Amina by the council who almost exiled her from the country, the man now noticeably plays up to the camera, stating that “that’s what Cameroon wants! We don’t want problems”. Vera’s prior empowerment over the abusive aunt juxtaposed with the oppression faced by Amina within this sequence epitomises the different roles in society held by women that Longinotto endeavours to bring to light.

In conclusion, Kim Longinotto’s filmmaking theories, employed throughout Sisters in Law, can be characterised at its core, by her proactive avoidance of intervention which is typically found throughout other documentaries. For example, if Nick Broomfield or Louis Theroux had made this film, their respective strong characters would be felt across the duration of the film. In the case of Longinotto, Sisters in Law’s approach allows for a much more subtle and thoughtful viewing experience, in which the viewer is able to draw their own conclusions through Longinotto’s implicit manner of filmmaking.

You must be logged in to post a comment.