Pulp Fiction (Quentin Tarantino, 1994) holds a highly influential place in the history of cinema. Winning the Palme d’Or at the 1994 Cannes Film Festival, the film was both a critical and commercial success. The film also revitalised the careers of both John Travolta and Bruce Willis, and its self-reflexivity and pastiche impacted the legacy of independent cinema forever.

To delve into Pulp Fiction’s cultural impact on cinema, we must first establish an understanding of the creative auteur behind it all: Quentin Tarantino.

While working in a video rental shop, Tarantino began his career by writing a number of screenplays after being encouraged by Lawrence Bender. Despite not amounting to a final product, this led to Tarantino gaining notoriety among producers. Because of this, he was able to write, direct, and act in Reservoir Dogs (1992) – a low-budget crime thriller featuring a dialogue-driven narrative set in a single location. Being screened at the Sundance festival that year, the film received immediate acclaim from critics.

Afterwards, Tarantino sold two of his previously written screenplays to studios to create both True Romance and Natural Born Killers, both of which featured Tarantino’s name heavily on the respective posters. Audiences soon eagerly await Tarantino’s next film, of which he kept important details other than the title – Pulp Fiction – under wraps. Upon release, the film received immediate critical acclaim and five Oscar nominations, with Tarantino winning the Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay. By this point, Tarantino had established himself as a highly prominent and notable auteur, going on to create seven more films, including: Kill Bill (2003), Django Unchained (2012) and Once Upon a Time in Hollywood (2019). Throughout Tarantino’s body of work, certain directorial tropes are ubiquitous throughout each, making the film indicative of Tarantino’s creative influence. Including nonlinearity, stylised violence, explicit language, and compiled scores featuring songs from the 1960s and 70s, many of these tropes can be traced back to the very start of his filmography.

With this in mind, Pulp Fiction can be defined as an experimental and postmodernist film. Featuring the majority of Tarantino’s directorial tropes, it acts as a prime exemplar of Tarantino’s body of work, establishing him as an auteur.

The film displays several interconnected storylines to the viewer in a nonlinear fashion now typical of Tarantino’s oeuvre. Cleverly building upon pre-conceived cliches of the crime genre, Pulp Fiction presents archetypal characters – such as a charismatic hitmen duo, a washed-up boxer, alongside a a stoic mob boss and his self-aware wife – in a fresh and unique narrative format.

A large portion of the dialogue featured throughout the film initially appears to be superfluous, as it doesn’t seem to drive the narrative forward in any meaningful direction. Considerable amounts of the film are dedicated to monologues centring around seemingly ‘mundane’ conversation topics, including: burgers, bible verses, and foot massages. In actuality, this dialogue richly characterises the archetypal characters of the crime genre presented to us. The dialogue has a snappy yet naturalistic style to it, through which the viewer is able to relate to and empathise with each of the characters on a deeper, parasocial level. This distinctive style of dialogue also further portrays Tarantino as an auteur, being present throughout his entire filmography.

The film additionally features very strong and graphic violence, a taboo that was seldom seen within the mainstream of cinema at the time. Being another common trope of Tarantino’s body of work, the extreme violence is presented in a humorous and exaggerated manner, creating a sense of irony.

Pulp Fiction’s status as a touchstone of postmodern cinema is due to a variety of factors – namely its extensive use of homage and pastiche to older works. Throughout the film, Tarantino makes subtle reference to many of his filmmaking inspirations – such as Hitchcock’s Psycho. The scene when Marcellus turns his head to see Butch in the car directly mirrors a similar scene from the 1960 classic. Similarly, the shot of the taxi licence when Butch is paying Esmeralda mirrors a similar shot in Taxi Driver (Martin Scorsese, 1976). Butch also uses katana to kill Maynard, a samurai sword seen throughout many Japanese films that inspired Tarantino, such as Seven Samurai (Akira Kurosawa, 1954).

The film’s score is also entirely compiled, being made up of an eclectic soundtrack predominantly from the 1960s and 70s. For example, Dick Dale’s rendition of Misirlou is famously used during the opening credits of the film, with Tarantino stating that “it sounds like rock and roll spaghetti Western music”. Each and every song used by Tarantino throughout the film garnered a renewed surge in popularity, such as Urge Overkill’s cover of Girl, You’ll Be a Woman Soon. This further demonstrates Tarantino’s influence as an auteur.

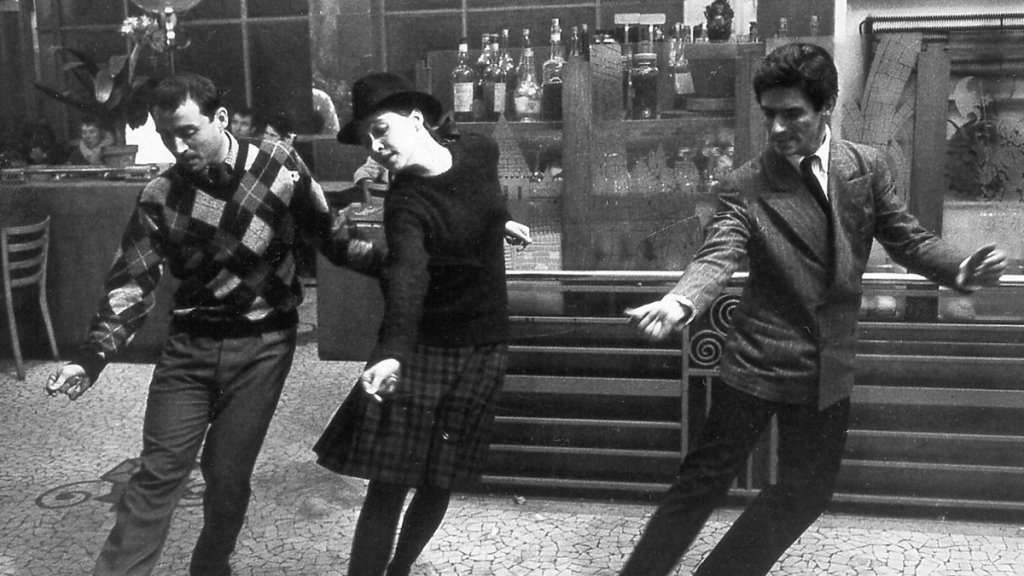

Tarantino’s use of pastiche throughout the film also contributes to Pulp Fiction’s postmodern status. A famous scene in the film displays Mia and Vincent dancing the twist to Chuck Berry’s You Never Can Tell. The cinematography and choreography of the scene parodies a scene in Bande à part (Jean-Luc Goddard, 1964) in which the three main characters decide to spontaneously dance in a crowded cafe. Another example is Christopher Walken’s monologue to a young Butch about his time in a POW camp, pastiching his role in The Deer Hunter (Michael Camino, 1978).